What the Picture Looks Like in Latin America and the Caribbean?

The short-term effects of COVID-19 cannot be ignored by anyone. Millions of Americans have lost their jobs, the French have to ask for permission to leave their house, the Vatican was empty on the first days of Easter and carparks have been transformed into temporary hospitals. All sectors of the economy are also affected, whether it is education, health, transport or hospitality- with the energy sector being no exception.

Electricity demand worldwide has also been witnessing unprecedented drops, now that most offices are closed with people working from home, that most public transportation has been significantly reduced and that large industries have interrupted their production due to fear of contamination between workers, or as a response to the drop in demand of certain products (clearly, some industries have been affected more than others- e.g. the dairy industry is suffering, whereas the entertainment industry is exploding).

Progressive drops in electricity demand

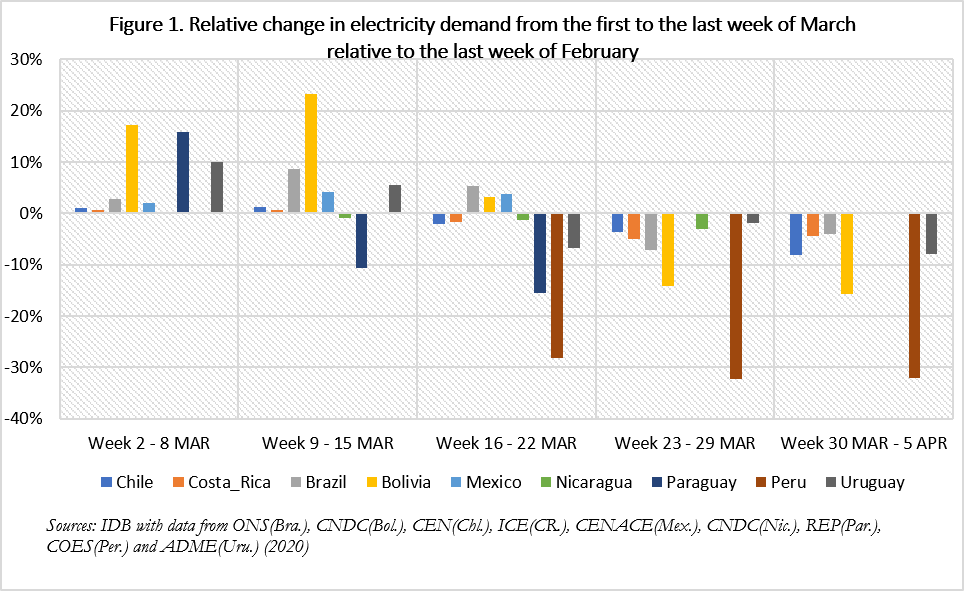

Using real-time electricity demand data for a set of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), we have been able to observe over the past month and a half the impact of the COVID-19 on the energy sector in the region and to put the trends in the context of national policies passed over this period of time. Figure 1 shows the relative change in electricity demand by week between March 2 and April 6 for nine LAC countries. The change is relative to the last week of February.

Heterogeneity in countries’ electricity demand response to the crisis

The trend is clear. Since late March, electricity demand has been decreasing in all countries, showing negative change rates in the two last weeks of March. We can also observe that in most cases the decrease has been progressive. However, in spite of a common downward trend, considerable heterogeneity can be seen across the countries, in terms of how electricity demand responded to the current crisis.

Whereas the analytical method used here is the same as that used to measure the behavioral changes of society when looking at the impact of holidays, strikes or meteorological effects on the demand of electricity, it is not exempt from shortcomings. The fact that demand by country is aggregated means that the figures fail to capture the different responses coming from the residential, industrial, commercial and public sectors. In addition, the origin of electricity consumption usually lies in how electricity-intensive the productivity of each sector and sub-sector is. This latter point justifies why countries like Bolivia, Chile and Peru, which all have large mining sectors that require heavy machinery, saw the largest drops in electricity demand over our period of analysis.

By contrast, economies that are more services-oriented tend to see a lower reduction in their electricity consumption, even though in the grand scheme the economic impact on the economies might just be as large as those whose productivity is more dependent on electricity consumption.

Measuring the impact of consumption profiles: what does it tell about how the economy is being impacted?

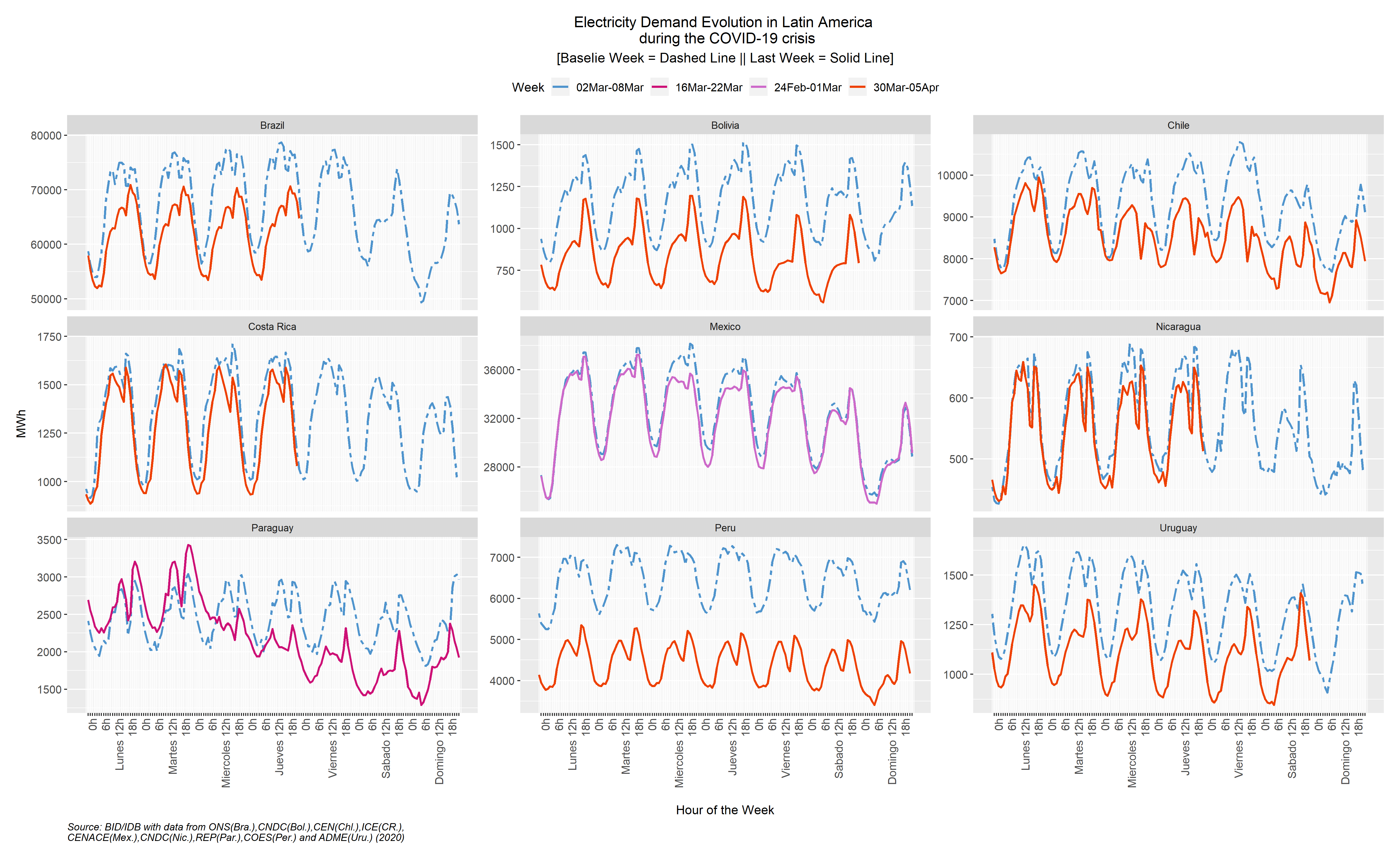

Despite the shortcomings in the present analysis of electricity consumption mentioned above, it is possible to know the hours of operation of each type of consumer (i.e. sector) and hence estimate who has significantly reduced their consumption. Generally speaking, the residential sector consumes less than companies and shops. This means that even if more people are now staying at home, leading to an increasing in domestic energy consumption, the aggregate response of electricity consumption to the crisis should still be going down.

In addition, the usual double peaks of consumption in one typical weekday in normal times are well-known. The first one happens around midday, when industrial activity reaches its highest. The second peak coincides with domestic consumption increases when people return home from work, as well as with the second manufacturing rounds and public lighting.

As Figure 2 shows, prior to the crisis and the announcement of some national policies, the double peaks of consumption were happening as expected during late February-early March. By contrast, as of the week of March 29, the picture looks somewhat different. The first peak has almost vanished, and the second peak still happens but at a lower level. Both findings show the decrease in consumption of the industrial sector, where the second peak is still pronounced because of the usual public lighting and post-work evening activities of households.

Figure 2. Comparison of the aggregate electricity consumption by day and hour

* Mexico, Nicaragua or Costa Rica retain the consumption levels because they had not taken measures during the period analyzed.

It is worth mentioning that the time passed between our two periods of comparison, that is between the 2nd and the 29th of March, is also the time where most LAC countries declared isolation or confinement. This is when most people started working from home and not at the office anymore, and where some industries had to suspend their activities. To give a few examples, in Peru it was on March 16, in Paraguay on March 20, and in Bolivia on March 26.

What next?

These drops in electricity consumption have several implications for the energy sector in LAC. In the short-term, it means a negative shock in the sector revenue. The impact in the middle and long term will depend on: (1) how healthy was the sector before the shock; (2) the size and the duration of the demand shock, (3) how the demand risks are shared among the players in the sector (it will depend on market design, regulation and contract clauses), (4) the policies for recovery.

To plan how policymakers should behave and prepare for the recovery, monitoring the demand behavior during the process and estimating (even if it is tricky at this moment) the size and duration of the shock are important. The estimation of the size of the revenue gap is a piece of relevant information that can allow policy makers to look for the best solution and to tailor it to speed up the recovery and avoid collateral effects, such as an energy sector solvency crisis.

Leave a Reply