If anything is clear in the development business, it is that attracting and retaining a qualified and motivated civil service is one of the hardest things to do. And the impact of not having such a work force is stunning if one believes the recent – and very illuminating and controversial – results from the paper by Tessa Bold and others on contract teachers in Kenya. Gabriel Demombynes from the World Bank wrote a very insightful blog on it.

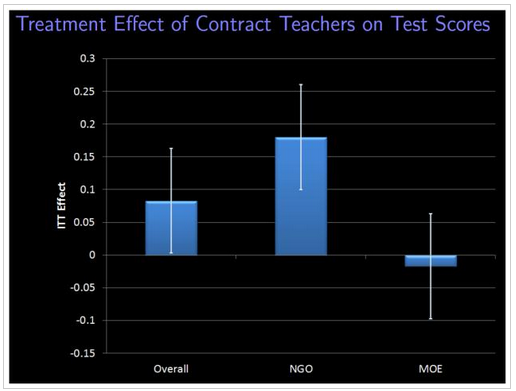

The bottom line: “the effect [on test scores] for schools where the contract teacher was administered by the NGO was 0.18 standard deviation, while for schools where it was implemented by the Ministry of Education (MOE), the effect was negative and statistically indistinguishable from zero.” Zero.

Both Bold – and her co-authors – and Demombynes, discuss at length the political economy implications of these results for scaling up successful interventions.

Regardless, the most important lesson is that we should do more rigorous evaluations working with governments, and reforming government service delivery is a critical piece in this Rubik´s cube in the long run. Effectiveness without scaling seems like clapping with one hand. And scaling without government does not seem plausible.

So what do we know, with hard evidence and rigorous methods on what works in reforming government service?

Not much and we need to know much more as my colleague Koldo Echebarría argued a year ago in this blog. So in future blogs we will comment intermittently on the emerging literature on rigorous evaluations of institutional reforms in the public sector.

Let´s start with civil service in Mexico.

A recent paper by Ernesto Dal Bo, Frederico Finan and Martin Rossi studies a recruitment drive for public sector positions in Mexico by randomizing salary offers and recruitment sites. This allows the authors to try and answer a set of critical questions on personnel selection, quality attributes, incentives and the monopsonistic traits in local labor markets.

The results from this experiment show that:

(i) cognitive ability and psychological traits are important predictors of candidates’ previous wages,

(ii) years of schooling and cognitive abilities are correlated, but the magnitude is small, and

(iii) cognitive ability is positively correlated with measures of pro-social behavior.

So it seems that there is no tradeoff between many desirable traits and cognitive abilities. Recruiters need not worry about Mr. Hyde here.

So if certain traits are correlated with higher wages, can higher wages be used to attract better candidates? By randomly assigning two different wage offers, the higher wage offer do attract better candidates as measured by higher previous wages, cognitive ability, public sector motivation and higher IQ scores. The paper also shows that the Mexican government faces a relatively elastic labor supply function with an estimated elasticity of 1.8, consistent with estimates from non experimental studies.

Finally, job acceptance is determined primarily by commuting or relocation distance and candidates, when weighing job offers, are more likely to accept if the municipality has better characteristics than the candidate’s own.

So higher salaries do attract better candidates in Mexico, while in Kenya contract teachers hired with lower salaries by NGOs show better performance than teachers hired by the Government with significantly higher salaries.

Governance and institutional designs and the structure of non-pecuniary incentives might be underlying these differences. Mexico is very different from African countries and ranks significantly higher in the World Bank’s Governance (Government Effectiveness) indicators.

And these governance and institutional differences go beyond the public sector. As Annie Duflo and Dean Karlan show in this article, management consulting helps small firms in Mexico and does not in Ghana, where effects dissipate after a year.

And one can think of institutional strengthening programs from the IDB or the World Bank as management consulting on steroids.

Knowing what works is critical and knowing if it will work if implemented by governments is essential for scaling and having an impact beyond an experimental setting. And knowing that what works in Mexico, might not work in Kenya is also important. External validity is not a given.

In Kenya, Mexico, and all developing countries from Abkhazia to Zimbabwe.

Leave a Reply