For nearly two decades between 1990 and 2018, women in Latin America and the Caribbean made substantial progress in reducing the large gender gap in the labor market. As female employment levels surged, and unemployment rates fell, labor force participation rates among women rose a full 25% and wage differentials dropped.

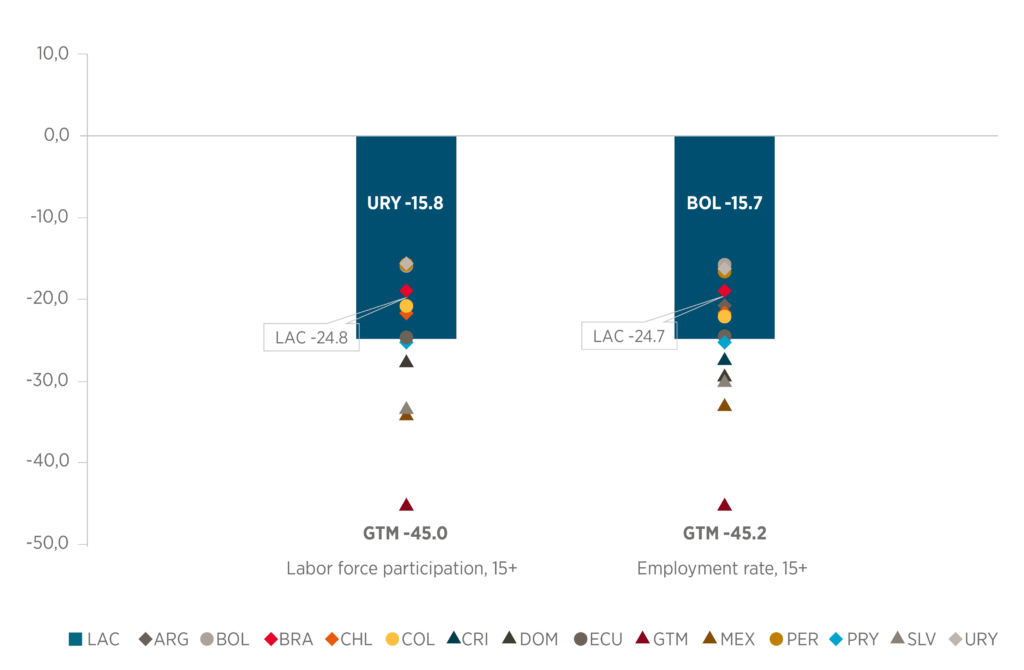

To be sure, this progress was insufficient to achieve equality and fulfill women’s aspirations. Women could still be found to a disproportionate degree in the informal sector and in low wage occupations, and a yawning gap of 25 percentage points on average between men and women in labor force participation marked the considerable distance still to be travelled towards equal opportunity. Nonetheless, women were making headway.

All that was threatened by the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused nearly 26 million people to lose their jobs in 2020 and inflicted an especially harsh penalty on women whose lopsided participation in low-productivity and informal occupations made them especially vulnerable.

The good news is that the pandemic, for all its trauma, failed to significantly knock the two-decade trend in declining gender gaps off course in most countries of the region. Still, in a subset of countries the gender gap did widen. And women in the region were harder hit in terms of employment losses in 2020 than men and were less likely to work in 2021 than they had been in 2019.

These findings in a recently released study have immense implications for women as they attempt to move forward on the road to equality. They also bear significantly on policies, ranging from child-care to education, that governments might take to even the playing field.

In the study we analyzed the evolution of gender gaps in the labor market during the pandemic in terms of labor force participation, employment, unemployment, informality, and labor income dimensions. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to process data from nationally representative household and employment surveys for 14 countries in the region and provide a comprehensive perspective on the effects of the pandemic on gender differences in the labor market. For 10 of those countries–Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Paraguay, and Uruguay–the data include 2021.

Figure 1. Female vs. Male Gender Gap in Labor Market Indicators for the Population Ages 15-65 in 14 Latin American and Caribbean Countries, 2019 (Percentage points)

Source: Calculations based on data from CEPALSTAT.

Note: ARG = Argentina, BOL = Bolivia, BRA = Brazil, CHL = Chile, COL = Colombia, CRI = Costa Rica, DOM = Dominican Republic, ECU = Ecuador, GTM = Guatemala, LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean, MEX = Mexico, PER = Peru, PRY = Paraguay, SLV = El Salvador, URY = Uruguay.

The gender gap for the labor participation rate and employment is measured as: gap = (TF – TM)t1, where T = indicator, F = Female, M = Male, and t1= circa 2019. For the unemployment rate the gender gap is calculated as: Δ gap = (TM – TF)t1, where T = indicator, F = Female, M = Male, t1 = circa 2019

How Did Labor Markets Fare in 2021?

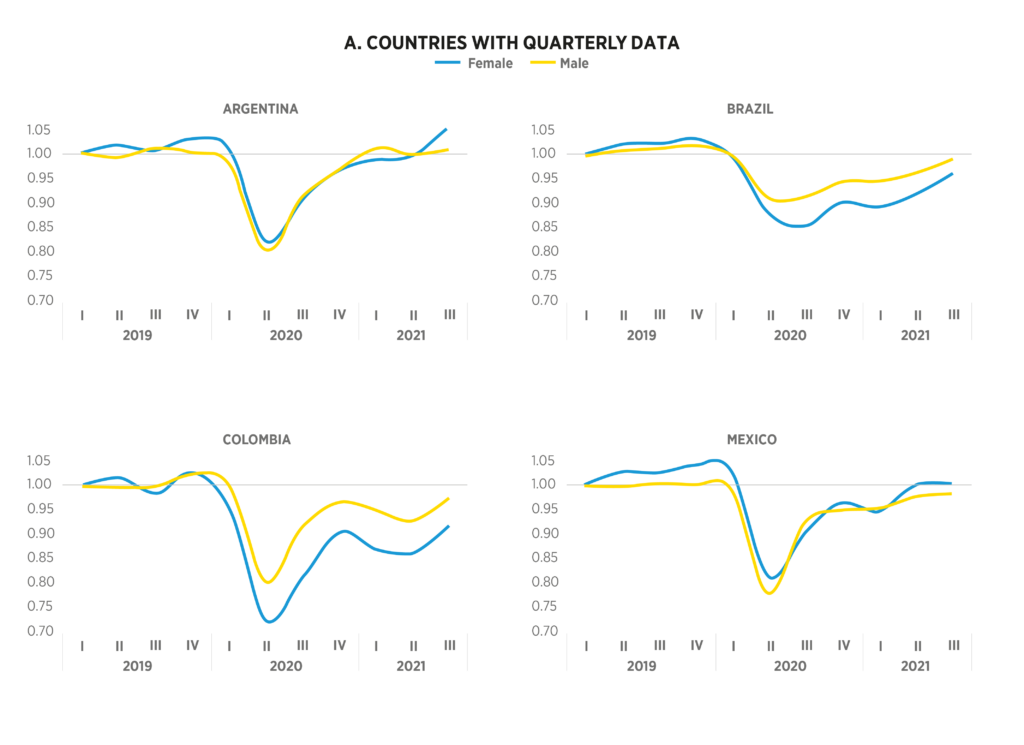

The pandemic did not significantly affect the trend in declining gender gaps in most countries (Figure 2, Panel a). But that was not true everywhere. In the case of Argentina and Mexico, the employment shock followed a similar path for women and men during 2020–2021. But men in Mexico suffered a slightly stronger shock in the second quarter of 2020. In both countries, women’s employment rate outpaced that of men, generating a positive change in the gender gap towards the end of 2021.

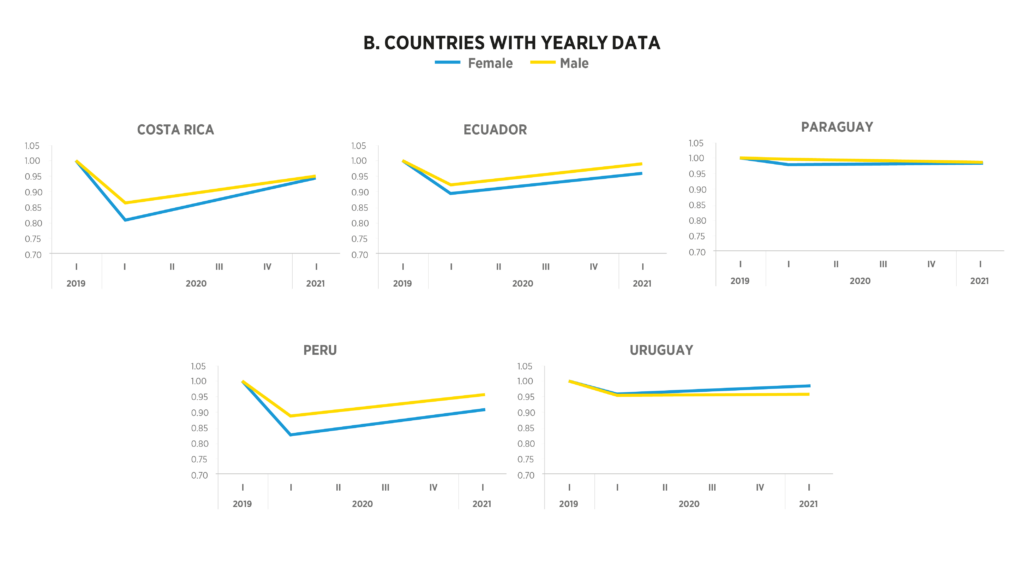

Meanwhile, in Paraguay and Uruguay, trajectories for men and women were practically the same, and there was even a slight shift in favor of women in Uruguay (Figure 2, Panel b).

In several other countries, however, our findings show reverses for women in terms of shrinking the gender gap. That was the case in Brazil and Colombia, where women were more affected by the shock in the second quarter of 2020 and had a relatively delayed catch-up in 2021. As we see in Figure 2, Panel a, the area between the curve representing the trajectory for women and the horizontal line with unit value is greater than for men for both countries. That implies larger accumulated job losses for women throughout the period with respect to the pre-pandemic period.

In Peru and Ecuador, men also gained on women in labor market results. This was due to the initial shock, and remained mostly constant thereafter, with larger accumulated losses for women. In Costa Rica there was no change in the gender gap when comparing the endpoints, but women experienced more accumulated job losses throughout the period.

Figure 2. Employment Rates for Women and Men, 2019–2021

Source: Authors’ calculations based on household and employment surveys. Guatemala is not included since we do not have information for 2020. Note: Employment rates are normalized to 1 in the base year.

These results, in effect, show a decidedly mixed picture. A closer look at the dynamics over the period reveals that the rebound for women in terms of employment levels was larger than for men in 2020–2021. That rebound apparently was not large enough to counterbalance initial losses (Figure 3). But, taking the region as a whole, the large increase in gender gaps that characterized 2020 was almost reabsorbed in 2021.

Figure 3. Estimated Change in the Probability of Men and Women Working in 2020 and 2021 Compared to 2019 (Percent)

Source: Authors’ calculations from household and employment surveys. Note: the figure plots the percentage change in estimated probabilities for men and women working in 2020 vs. 2019 and in 2021 vs. 2019 in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru.

Who Did the Pandemic Hit Hardest?

Women, of course, come many different walks of life, and differences in the pandemic’s effects reflect that diversity. Women with tertiary education, for example, were unsurprisingly less affected than women with lower levels of education. Women aged 14-24 were more affected than other age groups, as they were 19 percent less likely to work in 2020 and even with the recovery of 2021 were still 4 percent less likely to work. Women in urban areas were more affected than women in rural areas.

There were also shifts in types of employment as a result of the pandemic. Women in 2020 were more likely to work in the primary sector (extraction of raw materials) and less likely to work in the tertiary sector (the service and retail sector), a shift not fully reversed in 2021. Few differences emerge when considering household characteristics.

Looking Ahead

The pandemic inflicted losses in employment income that were considerably greater for women than men in most countries. Apart from the short-term effect of large, foregone incomes, this could leave significant scars and make women more vulnerable by depleting their family assets, affecting their future wages and/or reducing their possibilities of re-entering the labor market. This could be part of the reason why, despite the rebound, women were still less likely to work than men in 2021.

Significant challenges lie ahead. There may not have been large reverses in the trend towards gender gap reduction, but gender differences in the likelihood of working, access to formal employment, and wages remain sizable. Policymakers should take note. Women are more likely to work in the informal sector, and gender-neutral policies that favor formality in the region also favor women. Policies to combat informality include full-time childcare services, parental leave, and long-term care facilities for older adults, and should be combined with initiatives punishing wage discrimination and combating stereotypes. Continuous investment in accessible quality education is also crucial. Women with tertiary education proved to be especially resilient to the pandemic shock, and such investment can go a long way to creating a more resilient workforce and preventing women from exiting labor markets and suffering potentially detrimental long-term consequences.

Leave a Reply