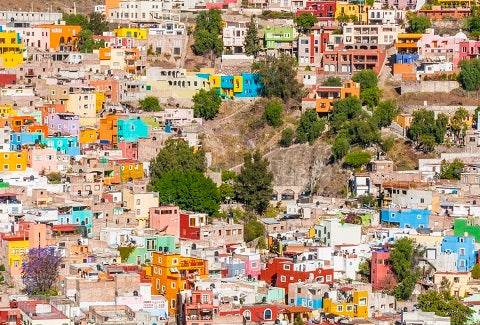

Imagine living in a neighborhood where some families have water and others don’t. Where half the streets are paved, and only some have sidewalks. Where street lighting exists only in certain areas, making it dangerous to return home at night or go out before dawn. Or where you have to walk very far to find a park, a football field, a health clinic, or a day-care center.

That is the reality of many Mexican neighborhoods. Although the national average for coverage of basic infrastructure services is above 90 percent, the statistic hides real levels of inequality within municipalities.

Today there are around 3,200 neighborhoods, also called polígonos in Spanish, with deficient access to certain basic urban and social services. Specifically, 17 percent of these areas are deficient in their coverage of piped water, drainage, and electricity.

Almost 60 percent lack public lighting, benches, sidewalks, or paved streets. Almost none of them have green spaces or meeting places where the community can get together to talk, celebrate special occasions, and spend time together in peace.

For more than 4 million families that live in these neighborhoods, residency in a formal city does not guarantee access to the services available in more consolidated urban areas. While all these families own their homes or rent them from the legal owner, 50 percent of them are still poor. And the absence of basic urban and social services makes them even more vulnerable.

In light of this problem, the Mexican government requested support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in 2003 to map the neighborhoods, identify deficiencies, determine priorities, and come up with a strategy for dealing with the most urgent areas.

This is how Programa Hábitat was born. Its main goal is closing the gap in the provision of urban and social services so as to integrate these families fully into the city.

Ever since, the IDB and Programa Hábitat have worked hand in hand to confront the neighborhoods’ challenges.

They have done so through the simultaneous construction of basic urban infrastructure and community centers administered by the municipality.

These centers are equipped with athletic courts and all-purpose spaces where numerous activities take place, ranging from classes for youth in computers, sports, and trades, to distance-learning workshops, and courses that help participants earn supplementary incomes in areas like hair dressing, sewing, and baking.

For those cases in which coordination with other Secretariats has been possible, day-care centers and health centers also have been established.

How has this been achieved? Through joint efforts between the federal government, the municipalities and the communities. Each has its share of responsibility: the federal government identifies those neighborhoods that are both poor and lacking in infrastructure.

The municipalities plan ways to close the gaps in each neighborhood, prioritizing investments and services while financing at least 50 percent of the initiatives themselves.

Finally, the communities play a central role in planning public works and actions, bolstering them with social oversight committees composed of neighbors who supervise the programs’ implementation.

Thanks to this joint effort, Programa Hábitat carried out initiatives in 350 municipalities and 1,400 neighborhoods while attending two million families from 2007 to 2013.

During that time, 45 million meters of paving and road construction and 25 million meters of potable water networks, drainage, and electrification were completed. And 1,800 community development centers were built or put into service, where each year around 7,000 social, recreational, and educational activities are undertaken for adults and children.

In 2009 the Mexican government and the IDB started to evaluate the impact of the program to determine if neighborhoods with deficiencies would have gotten the necessary attention in the program’s absence.

The evaluation was relevant because the municipalities, independently of the program, already had resources to invest in the neighborhoods. Within a universe of eligible neighborhoods, where no intervention had yet taken place at the beginning of 2009, 176 were chosen randomly for the program starting in 2009 and 194 were selected for the control group—where the intervention would take place only after the evaluation had closed.

The evaluation, which was completed in 2012, found that greater progress indeed occurred in neighborhoods benefitting from the intervention. In the 166 neighborhoods affected by the program, gaps were closed in a greater percentage than in a group of neighborhoods with similar characteristics where intervention was restricted.

The evaluation showed that the planning and focus fostered by the program resulted in the desired effect. Additionally, where Programa Hábitat was active, neighbors trusted one another more and had a greater sense of belonging, as they enjoyed community centers with a gamut of services and activities for adults and youth alike.

This story is part of our impact evaluations included in the document: Development Effectiveness Overview, a publication that highlights the lessons and experiences of IDB projects and evaluations.

Leave a Reply