In Panama, over a third of indigenous people are illiterate and school retention rates in indigenous areas known as comarcas are half the national average. The Government of Panama, with IDB support, is trying to change that by improving primary and secondary school infrastructure, training teachers, and providing learning materials.

Even under the best of conditions, accessing many of these schools can be difficult, so it is important to make the environment as appealing as possible in order to maximize learning and retain students. For example, 11-year old Magdiel Santos braves an hour walk through the woods—including crossing a river on a precarious bridge that is nothing more than a tree trunk—in order to reach the Batata school in the hills of Ngäbe Buglé, 300 kilometers northwest of Panama City.

“I want my children to continue studying to prepare themselves to be adults,” says Magdiel’s mother, Juana Santos, who has nine other children. “I was so happy when I saw the school after the work was done on it.”

Batata is among 46 primary or secondary schools in the comarcas of Ngäbe-Buglé, Emberá-Wounaan, and Kuna Yala that are being rebuilt or upgraded by the project. At the Batata school, the project put in a floor and replaced a leaky and noisy metal roof with a tiled one. An adobe hut that housed teachers who have to live at the school given its remote location was replaced by a brick-and-mortar house with a bathroom and electricity.

The project complements another government initiative to keep indigenous students in school by paying families a stipend of up to $200 annually for each student who stays in school until the secondary level.

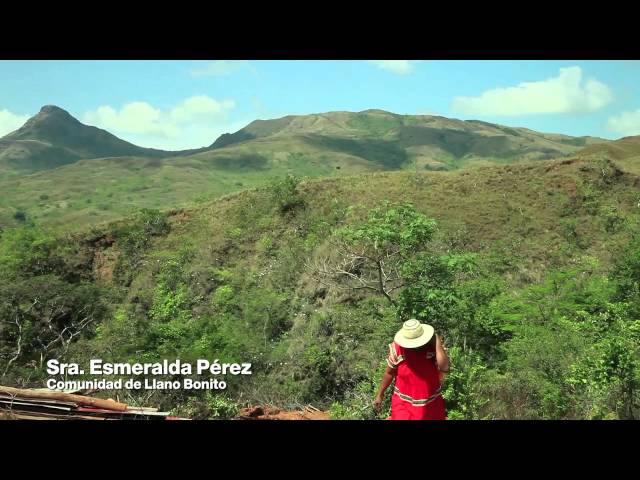

Since most of the schools under the project are in remote locations with poor road infrastructure, communities are getting involved in repairs by helping carry construction materials on their backs to the school site.

“We transported sand and cement for days, and we did this for the future of our children,” said Esmeralda Pérez, the leader of another indigenous community, Llano Bonito, that has benefited from the project.

The project is also supporting a comprehensive training program in mathematics and Spanish for over 32,000 teachers in collaboration with Panama’s Ministry of Education. Teachers are learning to introduce interactive educational methodologies and adapt didactic content to the socio-linguistic and cultural circumstances of each comarca. Teachers are also trained on formative evaluation techniques to better match learning activities with the real needs of their students.

The broad reach of activities under the $30 million project is expected to have a comprehensive effect on indigenous retention and literacy rates in Panama. In the isolated comarca of Ngäbe-Buglé alone, the project has built or repaired 17 schools, benefiting nearly 4,000 indigenous children. One of them—Magdiel Santos—might become the first among her nine siblings to complete secondary school.

Leave a Reply