Rodulfo J. Prieto is the co-founder of Laboratoria – a social organization that works to create a more diverse, inclusive and competitive digital economy in Latin America. Laboratoria is a member of the 21st Century Skills Coalition joined by different public and private organizations to promote the development of 21st century skills in Latin America and the Caribbean.

We are still at the early stages of this crisis. Nobody really knows when this will end or how the world will look like post COVID-19. There are many second and third order effects still unclear, both in terms of the virus itself and the economic and psychological impact of the social distancing and confinement measures in place. Yet, one may already take a few lessons from these first few months.

One noticeable aspect is how critical thinking has become a matter of high-stakes. Over the past weeks, many of us have had to make really tough decisions: Should we close or reopen our businesses? Should we all be wearing a mask while going outside? Should we show up for work even though basic safety and sanitary conditions are not in place? Should we return to work because our manager asks us to?

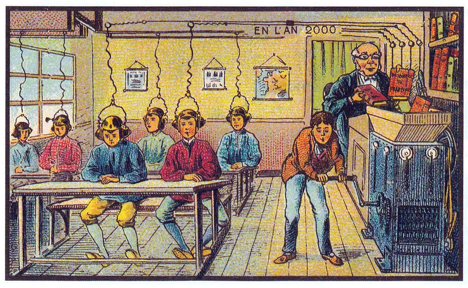

Critical thinking can be loosely defined as the rational and unbiased analysis of information to form a judgment and guide action. It’s what we use to answer the questions above. The Inter-American Development Bank, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Economic Forum, all claim that critical thinking is one of the most important skills education should focus on to prepare students for the jobs of today and tomorrow — it’s one of the “21st century skills”. The only problem we have is that our education systems are not designed to actively develop critical thinking skills. Why? Because, for the most part, education looks like this:

Image by Jean-Marc-Cote

Our school system focuses on telling students what to think, instead of how to think, and is more preoccupied in teaching answers than the art of inquiry, questioning and reasoning. Here are 3 important lessons regarding critical thinking that are missing in most schools today, and that — in the context of a pandemic — have become a matter of high-stakes.

- Sapere Aude:dare to think for yourself.

We used to live in a world where information was scarce. We relied on a few “authorities” —like the media or governments — that, by exercising a monopoly over information, acted as sole sources of information. We had two options: either we trusted the source, and therefore took whatever it said at face value; or we didn’t, and decided to disregard it entirely. There was little room for critically evaluating claims in detail. “From the middle of the nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century, the public lacked the means to question, much less contradict, authoritative judgments derived from monopolies of information” writes Martin Gurri in his book The Revolt of the Public: And the Crisis of Authority.

But times have changed. Thanks to the Internet, we now have direct access to information from an ocean of sources. To learn about COVID-19 and its implications we have, for example, access to data and analysis in websites like Our World in Data and Twitter threads like this one:

Today we have the capacity to question everything: every government policy, every statement by worldwide institutions like the World Health Organization (WHO), every piece by a great newspaper, is today up for questioning. This change in conditions is crucial because we’ve seen many world leaders unprepared to manage this situation and that have opted to play populist by minimizing the risk of the pandemic, spreading false or misleading information and downright disregarding social distancing measures.

The motto of the Age of Enlightenment, Sapere Aude (dare to know), immortalized by Immanuel Kant in 1784 in his essay “What is Enlightenment?”, is today as valuable as ever:

“Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another. This immaturity is self-incurred if its cause is not lack of understanding, but lack of resolution and courage to use it without the guidance of another. The motto of enlightenment is therefore: Sapere aude! Have courage to use your own understanding!”

So lesson #1: we can’t take at face value what authorities tell us — be it the media, public health organizations, our leaders or even our bosses. We need to think for ourselves.

- Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

On January 14, the WHO posted what has now been dubbed as an infamous tweet stating there was no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the (then) novel coronavirus. See tweet by @WHO:

Of course, a few days later, human-to-human transmission was indeed confirmed. This is a clear example of mistaking absence of evidence with evidence of absence. Not finding evidence of something is very different from finding evidence that something is not. If we haven’t found evidence of human-to-human transmission is either because: i) indeed COVID-19 does not transmit human-to-human, OR ii) it does, but we still have yet to prove it. When we see these claims, we often just think of the first possibility and forget about the second one. Big mistake. Especially since consequences are not symmetric i.e. the cost of overreacting to the virus early on (by assuming it did spread human-to-human) is significantly lower than the costs of underestimating the virus (by assuming it did not spread human-to-human).

So lesson #2: No evidence doesn’t mean no risk. Just because something hasn’t been proved yet, it doesn’t mean it’s not there. Given that outcomes of our decisions are rarely symmetric, we must always weigh the costs of error.

- In a complex and uncertain world, simplification is dangerous

This is a very complex and fluid situation. As the secretary general of the United Nations has stated, we are currently facing the worst global crisis since WWII.

First, there’s the risk of the disease and how it’s exponential growth is collapsing health care systems across the world. This goes beyond the official COVID-19 death tolls being reported by governments on a daily basis. As The Economist reported, official covid-19 deaths “still under-count the true number of fatalities that the disease has already caused”. In many places, official daily figures exclude anybody who did not die in hospital or who did not test positive… And even the most complete covid-19 records will not count people who were killed by other conditions that probably would have been treated successfully, had hospitals not been overwhelmed”. The risks from the virus also include the long-term effects of the disease. Yes, many people — especially the young — recover from it, but are there long-term effects? Do recovered patients suffer irreparable lung damage? Does it shorten your life expectancy? It will take years and longitudinal studies to get a clear understanding of this.

Second, the consequences of forcefully shutting-down economic activity — a key element of the “solution” many governments have implemented — can also be monumentally catastrophic. David Beasley, the Executive Director for the World Food Programme (WFP) recently warned that “at the same time while dealing with a COVID-19 pandemic, we are also on the brink of a hunger pandemic”. Can more people die from the economic impact of COVID-19 than from the virus itself? It’s definitely a possibility — especially for developing countries. All countries face a different context. Some have more fiscal resources than others, some have better health care systems, some have better testing capabilities, some implemented policies earlier. Each country needs a different strategy according to its context, but they all need to optimize for both problems.

So lesson #3: Most things are not simple in real life. Be skeptical of the analysis and recommendations from anyone that is oversimplifying this situation (e.g. it’s-just-the-flu).

The Silver Lining

Over the past decades, many individuals and organizations have aimed to disrupt education. Learning hasn’t been the same since Khan Academy and Coursera, for example. And many more education ventures have brought better experiences and opportunities for people across the world. Indeed, the work we’ve done at Laboratoria over the past 5 years has been our contribution.

Yet, there is still so much to accomplish. Think about how much phones, computers and automobiles have changed over the past 100 years. Now think how much classrooms have changed. This crisis represents the opportunity to finally disrupt the ‘system’. As Khan Academy founder, Salman Khan, has argued: ”the balance between in-person and online learning could be a ‘silver lining’ of this crisis”. Indeed, we have an opportunity to rethink how people learn and to build a new education model altogether. One which blends online/remote and in person experiences. One that enables students to learn at their own pace, that values individuality and fosters student’s appropriation of knowledge. One that puts critical and creative thinking at the heart of their learning experience, so students really learn how to think, not what to think.

We, at Laboratoria, will continue working to see this happen.

Stay tuned and follow our blog series on education and #skills21 in times of coronavirus. Read the first entry of these series here. Download the Future is now and keep an eye out for our news!

check this out it makes tutors and institute lives easy https://utobo.com is a SAAS based online tutoring platform, which helps institutions in creating courses and test series and helping them sell online

Tutors’ and institutes can conduct live classes, build courses and test series, sell it to the market with an e-commerce website, manage admission, accept fees online and offline.