Smart spending in education is an approach that seeks to generate greater impact on learning.

- Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) allocates 4.2% of GDP to education, with an average investment of $2,500 per student per year.

- But it is not only about increasing education spending; it is about directing resources toward what truly improves learning.

- Smart spending in education means maximizing the impact of resources invested in student learning and development.

For decades, the debate on education in Latin America and the Caribbean has revolved around a seemingly simple question: How much do we spend on education?

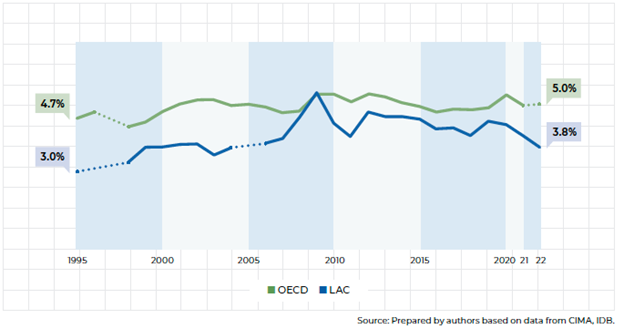

Yet this perspective, while important, is insufficient. Public spending on education in the region fell to 3.8% of GDP in 2022, the lowest level in more than 20 years. Post-pandemic recovery has been slow, while learning gaps equivalent to several years of schooling compared with OECD countries persist.

Figure: Public education spending as a percentage of GDP (OECD – LAC)

At the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), we know that when resources are limited, how they are used makes the difference between a stagnant system and a transforming one. We have worked with Ministers of Education and Finance, school leaders, and communities in 22 countries across the region. We have heard their challenges: schools without enough teachers, programs delayed by administrative hurdles, budgets unable to respond to the needs of the most vulnerable.

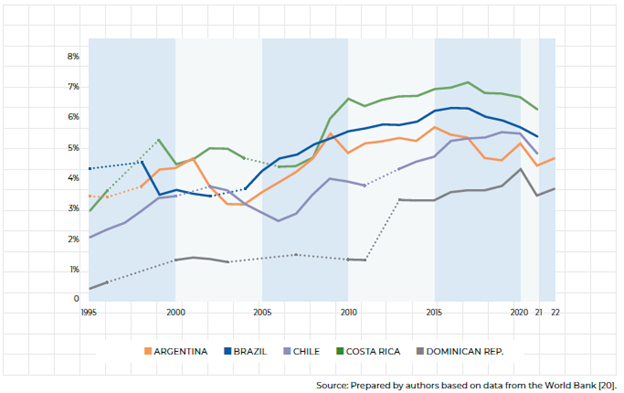

We have documented how some countries achieve more with less: Brazil is the only country in the region with sustained improvements in PISA (the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment) over the last 20 years, thanks to systemic reforms—while others, despite higher investments, have seen stagnant results.

These experiences motivate us to promote a new way of thinking about education financing. This is where the concept of smart spending in education comes in: a paradigm shift that not only asks how much we spend, but also how we sustainably mobilize more resources, how we distribute them, how we execute them, and how we ensure that these investments truly improve learning.

What is smart spending in education?

(Video in Spanish)

Smart spending in education means maximizing the impact of resources invested in student learning and development. It emphasizes efficient mobilization of resources, equitable distribution, effective execution, and robust monitoring. Simply increasing resources is not enough; how they are spent is crucial, especially for the most vulnerable students. Achieving smart spending requires balancing adequacy, equity, efficiency, and transparency in education financing.

The smart spending agenda includes four key areas:

1. Mobilizing resources sustainably

Education systems in the region face constant competition for resources with other sectors such as health, security, and infrastructure. This is compounded by fiscal volatility, which often hits social investment hardest.

Sustainable mobilization means designing fiscal frameworks that protect education even in times of crisis.

- Panama created the Education Insurance Fund, a dedicated tax on income that ensures stable flows.

- Colombia implemented social impact bonds, where private investors finance education programs and the government pays only if specific results are achieved.

- Brazil established FUNDEB, which not only redistributes resources among municipalities based on equity criteria, but since 2020, is permanent and will increase the federal contribution from 10% to 23% by 2026.

- In the Dominican Republic, fiscal pacts have guaranteed political commitment to keep education spending above 4% of GDP.

These examples show that financial sustainability depends not only on political will, but also on institutional design.

Figure: Public education spending (as a percentage of GDP)

2. Distributing with equity and technical criteria

In many countries, education budgets are still allocated using historical or discretionary criteria. This generates persistent inequities: rural schools without enough teachers, vulnerable communities with poor infrastructure, and overcrowded urban schools without additional resources.

Smart spending requires that distribution be based on objective formulas, incorporating variables such as enrollment, socioeconomic level, geographic location, and vulnerability status.

- Chile’s Preferential School Subsidy Law (SEP) allocates 70% more resources per vulnerable student, using updated socioeconomic data at the individual level. The result: the learning gap narrowed by the equivalent of one year of schooling.

- In Ecuador, the “optimal staffing plan” system uses algorithms to assign more than 30,000 teaching positions in minutes, eliminating political discretion that previously took months.

These examples show that it is not enough to increase the total education budget: it is essential to ensure that funds reach those who need them most.

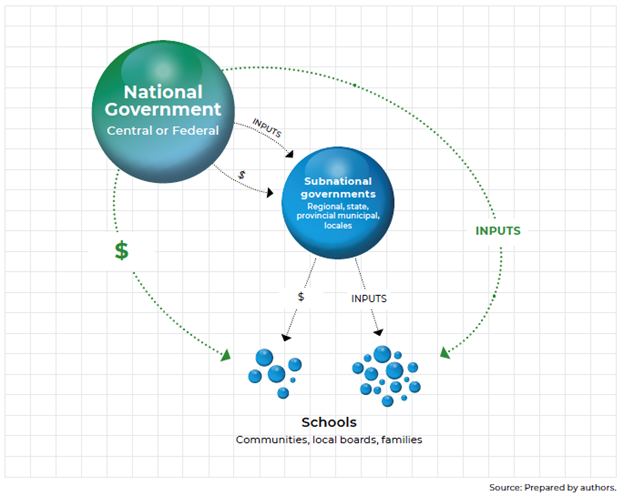

Figure: Distribution of education resources

3. Executing with efficiency

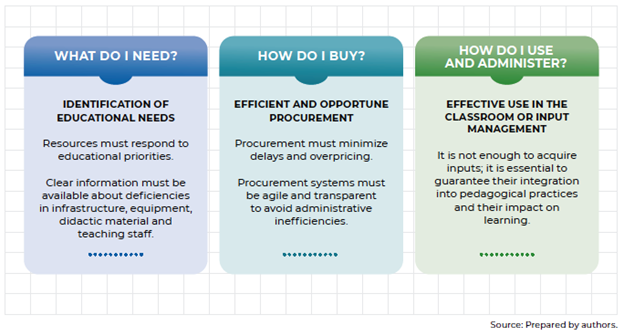

Often, there is a wide gap between budget approval and actual arrival of funds to schools. Complex administrative processes, low management capacity in ministries, and bureaucratic hurdles slow down the impact of spending.

In São Paulo, for example, purchasing a pen through centralized procurement required specifying 32 technical characteristics to ensure quality—creating administrative paralysis.

The IDB has identified cases where up to 30% of approved education resources go unspent within the fiscal year. The issue is not only about money, but also about management capacity.

Smart spending promotes modernizing education management systems through digital tools, multiyear planning, capacity building, and decentralized execution mechanisms.

- In Peru, the Performance Commitments (CdD) program links resources to specific goals while also providing technical assistance to subnational governments to achieve them.

- In Colombia, Bogotá’s SIDRE consolidates the needs of 406 public schools into a digital platform, dramatically reducing procurement times.

Efficiency is not a luxury; it is a condition for every peso to reach where it is needed.

Figure: Key factors for efficient budget execution

4. Monitoring real impact

Measurement is essential, but it must strengthen rather than paralyze. Too many reports, indicators, and controls can create administrative paralysis instead of driving improvements.

The IDB promotes smart monitoring systems that combine technical rigor with operational flexibility, integrating both quantitative data (learning outcomes, enrollment rates, infrastructure) and qualitative data (teachers’ perceptions, family satisfaction, local innovations).

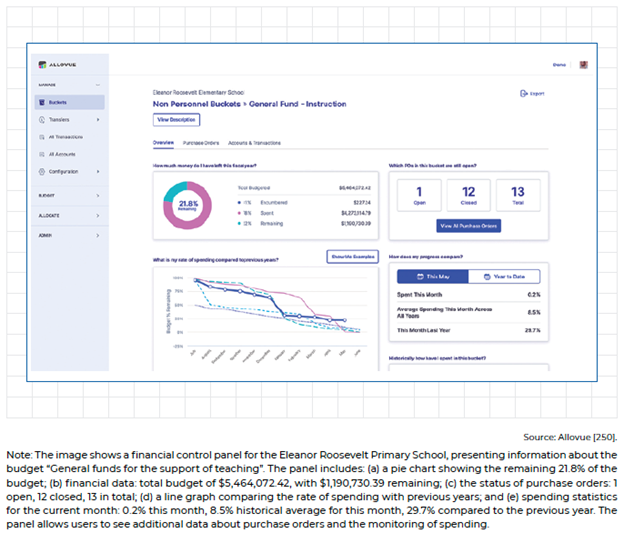

- An illustrative case comes from Jamaica, where the Manage platform, piloted in 51 schools with IDB support, connects budget execution with school performance indicators and learning outcomes in real time.

More than a control exercise, monitoring becomes a strategic instrument to ensure that every dollar invested generates real value in classrooms.

Figure: Manage platform, pilot project in Jamaica

This case confirms a core lesson of the smart spending approach: monitoring must serve learning, not bureaucracy. Jamaica shows that when financial and pedagogical tracking is effectively integrated, education systems are strengthened, and the principle that “every peso counts” becomes a daily practice.

Opportunity starts with education

The pandemic, insecurity, and fiscal constraints have tested our education systems but have also opened a unique window: the opportunity to rethink how we finance education so that it not only survives crises but emerges stronger from them.

At the IDB, we are convinced that now is the time to promote smart spending in education. It is not only about numbers, but about a commitment to equity, quality, and efficiency. It is about ensuring that every child in Latin America and the Caribbean can learn—regardless of where they were born or which school they attend. That is why we will continue supporting the region in this transformation.

Download the publication here and learn more about this approach.