Providing universal water and sanitation services is a goal that all Latin American and Caribbean countries share. To achieve it, we need to collect data that lets us clearly measure the progress and the gaps we need to address.

By Analia Gomez Vidal y Jesse Madden Libra*

Achieving universal water and sanitation services are goals common to all countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. But so far, measuring progress towards these goals seems out of reach. In the technical note “Water and Sanitation Services in Latin America and The Caribbean: An Overview of Databases and Information Gaps”, written by the knowledge team in the Water and Sanitation Division of the IDB, we find that only 4 of the 22 household surveys examined in our region include response options that allow for proper classification of improved water sources and sanitation facilities, following the definitions used by the Joint Monitoring Programme. Only 41% of the studied household surveys specifically ask about potable water, while 68% of the surveys ask if sanitation facilities are exclusive to the household.

Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) establishes universal access to water and sanitation as a goal, as well as the sustainable management of water resources, but how can we measure the associated indicators if we do not collect the necessary data?

There are two important obstacles to improving measurements for SDG 6.1 and 6.2: the variety (heterogeneity) of definitions with respect to classifying water and sanitation services, and the limitations of existing sources. Our team wrote this note to address these obstacles. In this technical note, we identify data sources and current information gaps, and establish specific guidelines that correspond to the necessary indicators for measuring SDGs.

Our team designed and administered an original module on water and sanitation that was part of the AmericasBarometer 2018-2019 survey by LAPOP at Vanderbilt University. This initiative aimed at collecting original data that helps close the information gaps identified. The exercise focused on comparing household surveys, and the lessons learned through that process informed the design of this survey and its following iteration in 2021.

The publication includes recommendations for future implementations in other surveys in Latin America and the Caribbean, including household surveys.

The biggest difficulty to quantifying access to improved water and sanitation is the complexity of indicators. The categorization of safely managed drinking water includes four dimensions; water must be: from an improved water source, available on-premises, available when needed, and free from fecal and chemical contamination. Each of these criteria comes with its own definitions and sub-definitions, making it necessary to collect very specific data to properly classify the information collected. But it is also difficult for complementary reasons, such as the diverse framing of the questions. incorporating the purpose for water, or how much time it takes to access water.

Similarly, the definition of safely managed sanitation includes three dimensions: access to improved sanitation facilities, access that is exclusive (i.e. unshared with other households) and facilities that properly handle of waste, either via treatment and elimination of waste in situ, temporary storage followed by emptying and transportation to treatment off-site, or transportation through sewage system treatment off-site. One last factor in water and sanitation that is often ignored, but it is key in the context of a pandemic, is the existence of handwashing facilities.

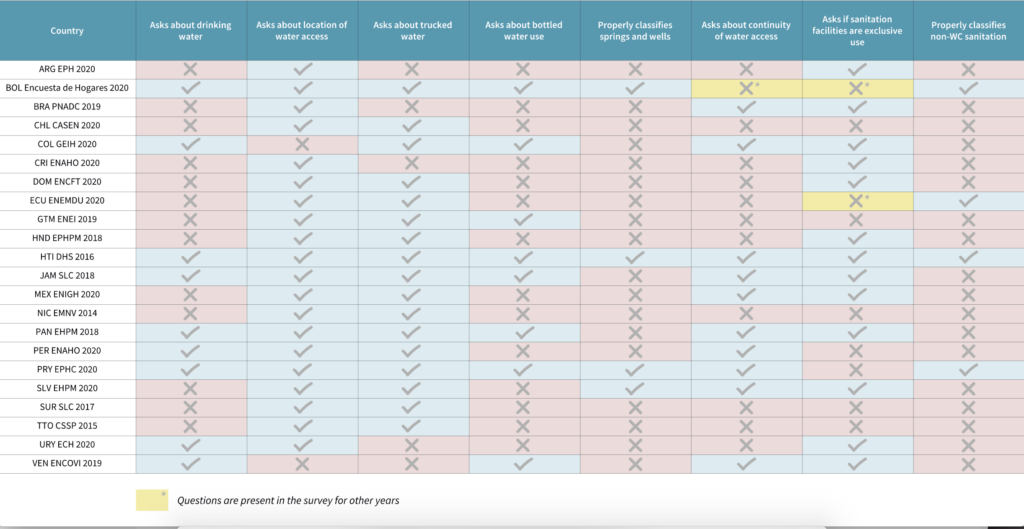

The first step to write this publication was to identify the available official data sources on water and sanitation, and how these definitions are measured. For each country, we selected the most recent household survey that included a module on water and sanitation, along with other relevant dimensions for complementary statistical analysis. Most of the included surveys were from 2018, although there were exceptions that would go from 2014 to 2019. Table 1 shows a summary of our analysis in the most relevant categories.

The comparison exercise demonstrated high regional variation in designing survey questions related to SDG 6.1 and 6.2, preventing comparability and consistency in the analysis of indicators. In the document, our team highlights indicators and questions that model the ideal survey questions for collecting the information necessary.

Additionally, we included five strategies that our team implemented in the design of an original module in the AmericasBarometer 2018-2019. These strategies were:

- differentiating the use of water sources,

- distinguishing between types of sources,

- measuring continuity of service,

- differentiating sanitation facilities and destination of excrement, and

- measuring exclusivity of facilities.

Data obtained through this survey currently complement the information provided by the Water and Sanitation Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean (OLAS in Spanish) and will be available on the platform in the coming months.

Our publication reflects a multi-year empirical exercise that our team has been working on to identify available data sources and address information gaps in the water and sanitation sector. It is clear that there is a lot of work to be done to rigorously measure the SDGs and provide a refined diagnosis of current and future needs. This publication offers clear guidelines, informed by the JMP and our lessons learned. We believe that this work is an opportunity for growth in our sector, and we invite you to implement these guidelines in surveys on water and sanitation at local, national, and regional levels.

Collecting comparable, consistent, and trustworthy data is essential to define where we are, and where we are going, on the path toward achieving SDG 6. More and better data means better informed, and more effective, policymaking. Our data is coming in like a slow drip, but we need it to flow in a steady stream to close the information gap.

*The authors are consultants at the Water and sanitation division at the IDB, based in Washington.

Leave a Reply