For many countries in the Caribbean region, tax policy and tax administration reforms have been a long overdue task. Given the current situation worldwide, the Caribbean countries are now more than ever faced with the critical need to improve their capacity to collect and manage revenues.

Achieving this will require the adoption of more efficient and modern institutional arrangements in both tax policy and operational aspects of tax administration and the promotion of digitalization at all levels.

Such reforms are addressed in detail in the first chapter of the new IDB book “Economic Institutions for a Resilient Caribbean”, which lays out an agenda of fiscal, monetary and financial reforms for the region to promote sustainable development

Why Caribbean Countries Have Low Tax Revenue Levels?

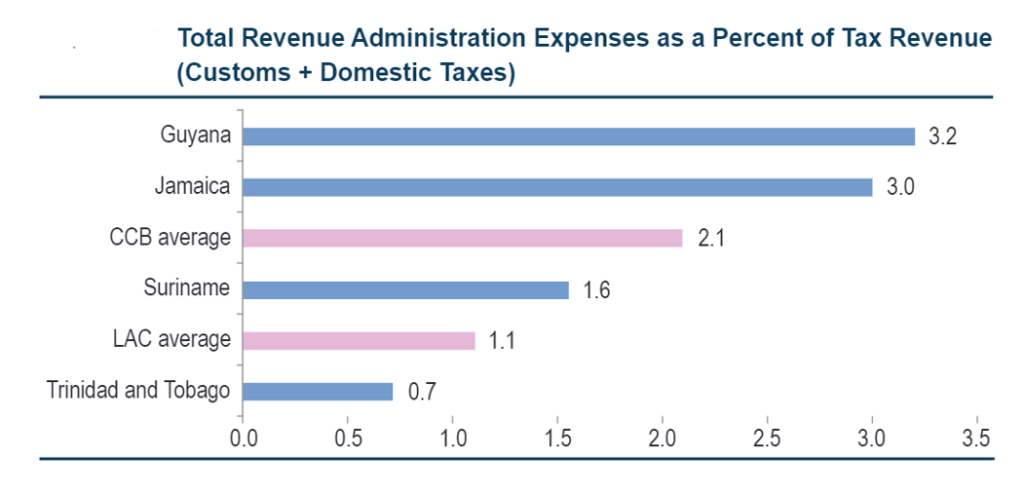

The rate at which tax revenues increase over time depends on the tax structure, the quality and capacity of tax administration, and the pace and nature of the country’s economic growth[1]. Even in the presence of structural differences between countries[2], the lack of integration, high statutory tax rates, proliferation of exemptions, incentives, deductions, allowances, and discretionary waivers have been consistent elements that muddles tax structures in the Caribbean. All these factors have contributed to low levels of tax revenue in the region, complicating tax administration collection (see figure below) and increasing taxpayer compliance costs.

Tax administrations (TAs) in the Caribbean are responsible for collecting around 65 percent of the total government revenue. In Guyana and The Bahamas these percentages are as high as 90 and 76 percent, respectively. Thus, the effectiveness of Caribbean TAs and their capacity to manage and boost these revenues are critical for fiscal sustainability in the Caribbean region.

Do Institutional Arrangements Matter?

A key ingredient behind the success of TAs in OECD countries (e.g., Estonia, United Kingdom, South Korea) and Latin America (e.g., Chile and Mexico) has been the institutional arrangements that enable them to function more efficiently. These include not only the governance model (the way the TA is organized to perform its functions) but also the legal framework that empowered them legally and politically to improve their effectiveness and speed up the process to enforce tax collection.

On this front, the establishment of more autonomous and flexible governance models stands out. There has been a growing trend to separate TAs from the ministries of finance by implementing Semi-Autonomous Revenue Agencies (SARA).

The main reason is that TA within the Ministry of Finance (MoF) typically faces administrative limitations that affect their operations and flexibility (lack of budgetary autonomy and control over staffing, limitations on procurement, and a limited capacity to adopt and acquire technological systems and implement reforms and operational policies, among others).

However, the experience of tax administrations like the Estonian Tax and Customs Board (ETCB) -a single directorate in the MoF – shows that a limited degree of autonomy has not been an impediment to displaying high levels of performance on most indicators surveyed by OECD (2019)[3].

Moreover, it has not been an impairment to advance reforms (especially in digitalization) that have been hailed by the literature as successful[4]. Also noteworthy is the adoption of segmentation strategies such as Large Taxpayer Offices (LTOs) and the shifting from a tax – type organizational structure to a function – based one (support and operational functions).

In the case of the Caribbean, despite the efforts for institutional reforms many old institutional arrangements remain, which hinders the scope and effectiveness of TAs. This has led to low levels of operational performance, such as low on-time filing and payment rates, high levels of arrears, low audit rates and deficient revenue management.

Today, TAs in Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago and the Bahamas are located within the MoFs, where they lack budgetary autonomy, control over staffing, and access to trained staff. These entities face procurement limitations, hindering their capacity to adopt and acquire technological systems, as well as implement reforms and operational policies.

Other TAs in the region (Jamaica, Guyana and Barbados) have established SARAs with a greater level of autonomy, but in the case of Guyana and Barbados, this has not been enough to enable the effective adoption of a risk management approach, strategic management planning and performance assessment.

The Quest for a Progressive Digital Transformation: A Bumpy Ride

It is becoming increasingly clear that encouraging digitalization is both a necessity and an opportunity for tax administrations to enhance their overall performance. Moving from paper to electronic, from electronic filing to pre-populated returns, and from returns to no-touch and automatic filing.

The future is machine-to-machine (M2M), where the tax authorities will crave data, not tax returns. However, this will not happen overnight, and the international experience shows that tax authorities face the challenge of adopting new technologies in accordance with their capacity to absorb them.

Information Technology (IT) will be the backbone of digitalization, yet there are also numerous difficulties and obstacles beyond IT infrastructure that prevent tax administrations from further advancing their digital transformation. These include among other things: outdated laws, budget constraints, limited human resources (lack of technical training), and the inability to respond to time-sensitive operational changes. To overcome these obstacles and move forward in their digital journey, tax administrations must implement robust change management, workforce development, and institutional capacity-building plans.

In the case of the Caribbean, TAs have been slowly implementing technology changes. In many cases these TAs are in the early stages of digitalization and have concentrated their efforts in updating their IT systems and taking crucial steps towards automation by establishing basic electronic services. However, activities such as the use of artificial intelligence and extensive use of third – party information (cross checking) are in infant stages and are not routinely performed. Moreover, TAs in Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago do not have yet the institutional arrangements and the legal power to enact the mandatory electronic filing of tax forms and customs documents, as well as e-payments of taxes and customs duties.

Caribbean TAs have a long way to go in the digital era, but they can benefit from examining the approaches, successes, and missteps of their counterparts in other countries and regions including Estonia, Belgium, South Korea, Ireland, Norway, Russia, South Korea, Mexico, Brazil, and the United States. The experience of these countries shows that the process of digital transformation is a well-planned, hands-on operation that integrates new technology with existing systems and introduces management with empathy toward people and procedures.

Several tax administrations worldwide are keeping pace with digital trends and allowing digitalization to permeate all core processes[5] from taxpayer registry to revenue management. In this front, critical innovations such as big data, data analytics and artificial intelligence are allowing tax administrations to automatically cross-check information with third-party data. They are also improving auditing; identifying taxpayer behaviors and preferences to obtain a 360-degree view of taxpayers and deliver better and more targeted taxpayer’s services; improving debt management; assessing performance and operations to support decision-making; conducting policy evaluation; developing early warning systems; and fighting fraud and intentional misuse of identity[6].

Finally, Caribbean countries will also need to consider how to address new challenges that arise from digitalization such as data quality and ability to store and process massive quantities of information in a secure manner. For instance, the ability to generate and receive real time data means that in some cases the information may not be “clean” or structured.

The question remains whether tax administrations are ready to receive large volumes of data, clean them, store them, and use them efficiently and safely as new cybersecurity threats arise. Furthermore, as more timely information is collected and demanded from taxpayers, their expectations to receive faster and timely responses to their requests and inquiries increase, so tax administrations need to be ready to undertake operational changes to meet these demands.

Roadmap: Policy Measures to Modernize and Strengthen Tax Administration

To sum up, the Caribbean needs to increase its tax collection to be able to build its economic resilience and improve the government’s ability to provide better goods and services to its citizens. The region needs to advance on long overdue institutional reforms to improve its tax policy and tax administration.

Implementing such reforms will be challenging and will take time but they are possible and will pay off handsomely, especially in a world emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. Below Is a list of ten policy measures to jump start this transformation in the region:

- Keep it sound and simple: Simplify the good connection between tax policy and tax administration, and curb exemptions.

- Invest on organizational reforms: Undertake and speed up institutional organization reforms and modernization processes and commit to them at all levels (including inter alia: adoption of new organization arrangements or enhancing of existing ones in favor of greater flexibility to implement changes, addressing restrictions on staffing and procurement, improving training and education programs).

- Data is king: Improve taxpayers’ registry, data integrity and expand access to external data sources.

- Create a digitalization strategy: Strengthen the IT infrastructure and design and implement a comprehensive and overreaching digitalization strategy.

- Risk management is gold: Adopt a risk-based approach (risk identification, assessment, and management)

- Get to know your taxpayer: Improving and strengthening voluntary compliance requires a strategy that focuses on enhancing knowledge of taxpayers’ behavior and establishing better taxpayer’s service.

- Keep a close eye on auditing: Improve tax audit process and compute the tax gap.

- Be accountable and transparent: Publish annual reports and boost efforts on international taxation (exchange of information and implementation of BEPS framework)

[1] Bird, R., and S. Wilkie. 2012. “Designing Tax Policy: Constraints and Objectives in an Open Economy.” ICEPP Working Paper No. 1224. International Center for Public Policy. Available at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/icepp/78/

[2] Caribbean countries like The Bahamas and Barbados rely heavily on trade taxes, accounting for 43 percent of the total tax revenue in the form of numerous statutory rates and tariffs. Meanwhile, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, and Guyana collect the most from income-based taxes. Heavily invested in nonrenewable commodity exports

[3] OECD. 2019. “Tax Administration 2019: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies.” Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/tax/administration/tax-administration-23077727.htm

[4] For more information see: Kästik, T. 2019. “The Impact of Digital Governance on the Business Environment: The Case of Estonian Tax and Customs Board.” In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (April). Available at https://doi.org/10.1145/3326365.3326430, and Joshi, A., and J. Ayee. 2009. “Autonomy or Organization? Reforms in the Ghanaian Internal Revenue Service.” Public Administration and Development 29(4): 289–302.

[5] Registry and tax database, Effective Risk Identification, Assessment, and Management, Delivery of taxpayer’s services to support voluntary compliance, Tax returns , Tax payment processing, Reporting and Revenue management.

[6] McKinsey & Company. 2018. “Four Innovations Reshaping Tax Administration.” Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/four-innovations-reshaping-tax-administration and OECD. 2016. “Advanced Analytics for Better Tax Administration: Putting Data to Work.” Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/publications/advanced-analytics-for-better-tax-administration-9789264256453-en.htm

Leave a Reply