The state-owned enterprise (SOEs) sector in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is struggling financially and suffering from political intervention. More than 40% of such enterprises have reported annual losses for several consecutive years in the past decade.

The crisis has had important, and sometimes de-stabilizing impacts in the region. For example, heavy losses at state-owned enterprises have hurt solvency of certain countries, forcing them to seek IMF financial support. In other cases, political interference has prevented SOEs from increasing their prices or cutting their loses, hurting their financial situation and forcing rating agencies to downgrade their debt rating.

The three problems SOEs face

We researched this topic in our new book Fixing State-Owned Enterprises: New policy solutions to old problems. The new database of financial performance of SOEs in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and meetings with practitioners in the region revealed three overarching problems of the region’s SOEs:

First, the SOE sector is large and these enterprises have a lot of political clout. SOEs in Latin America are large relative to the size of their economies and this makes them important and hard to reform owing to the political clout they carry. For instance, SOE assets to GDP are 16 per cent in the region, with significant variance (e.g., in Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay they are around or above 20 percent of GDP). Additionally, our rough estimates of aggregate SOE expenditures to GDP show that in Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Jamaica, and Uruguay, SOEs spend more than 10 percent of GDP to cover their costs.

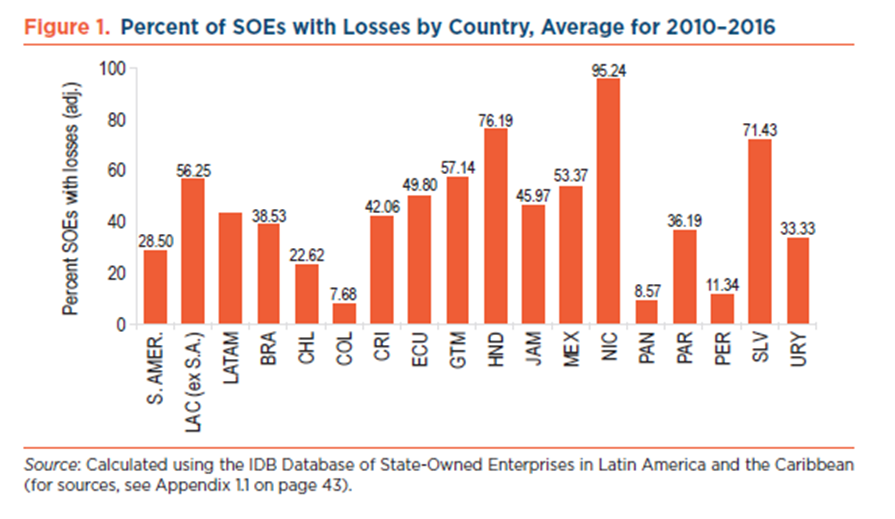

Secondly, SOEs are inefficient and show systemic losses. According to our calculations, 43 percent of SOEs in the region report losses every year (net of fiscal transfers) and for some countries this can be up to 70 percent of SOEs, as shown in Figure 1. In any given year, SOEs could require between one third to one percentage point of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in fiscal transfers to cover their losses. Moreover, every few years the largest SOEs require even bigger transfers to recapitalize their balance sheets. SOEs are also inefficient relative to the performance of their private peers. In industries in which we can compare private firms to SOEs in a like-to-like comparison using matching techniques, such as telecommunications, ports, electricity generation, oil and gas, and airports, we find that SOEs tend to underperform their private counterparts significantly. SOEs tend to have worse financial performance and also accumulate large liabilities relative to the size of their home economy.

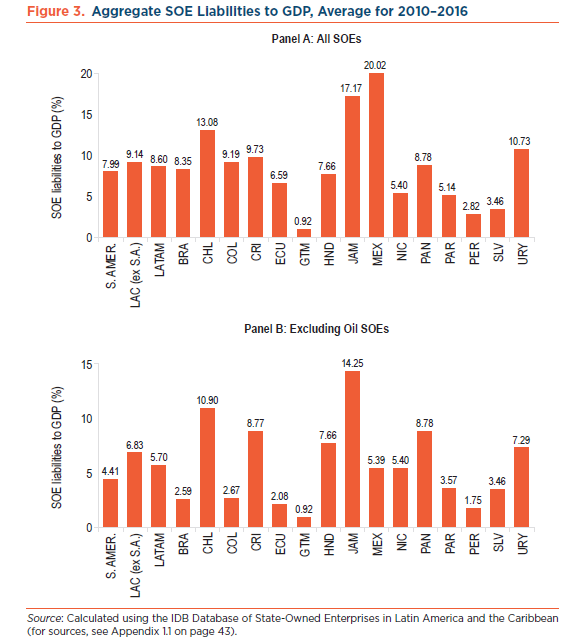

Thirdly, SOEs pose fiscal risks for their governments. They generate what we call cash flow risk, as the volatility in their net income puts them often in need of fiscal transfers to cover losses or to recapitalize the enterprise. Second, there is a contingent liability risk that stems from the size of the stock of liabilities of SOEs, either relative to GDP or to the size of the government budget.

SOEs end up accumulating large liabilities (as a % of GDP), which can be translated into fiscal risk. Figure 3 shows the size of total liabilities to GDP across countries. Panel A shows the size of SOE liabilities to GDP for all firms and these contingent liabilities should be a cause of serious concern. Even when we exclude oil companies, as shown in Panel B, SOE liabilities are close to 10 percent of GDP in many countries. This makes the SOEs we study too big to fail, but more importantly, too big to be bailed out.

Why SOEs are inefficient?

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) face two types of problems, from an economic point of view: information asymmetry and poor fiscal governance related to the discretion of SOEs and the government to extract resources from each other.

This problem of information asymmetry arises because, in many countries, there is no centralized system to collect and publish the financials of SOEs, and in many cases, SOEs report late or do not report regularly. This creates a problem not only because governments cannot correct the course ex-ante, but also because ex-post, the balance sheets of these SOEs are too large and governments realize when it is too late.

On the other hand, across the board, there is a problem of fiscal governance. Most SOEs in Latin America are funded directly from the government’s budget, with few or no rules to control such transfers. Therefore, the financial relation between SOEs and the government has enough discretion to operate as a de facto soft budget constraint, with significant cash flow and contingent liability risks.

The discretion in the fiscal relation between SOEs and the government allows governments to extract surpluses from SOEs on an ad hoc basis, leaving the SOEs either with losses, or with little capital to fund their own projects. The shortfalls are usually then covered by expected and emergency fiscal transfers that contribute to the unpredictability of SOE aggregate results.

In our research, we provide a practical way to solve either asymmetry of information problems in the monitoring of SOEs or solutions to reduce the discretionary nature of the fiscal governance of SOEs.

An innovative methodological and theoretical approach

Our research, based on SOE financials in the region, highlights their performance problems, the lack of transparency about SOE performance in many countries, and the sizable amount of fiscal transfers SOEs receive in large and small countries to cover losses and to cover up what on paper are bankrupt firms.

Using a simple agency framework to think about SOEs, considering both monitoring problems and fiscal governance issues, we provide a model of centralized monitoring of SOEs that helps correct for some of the current problems. We provide empirical evidence to show that countries currently using this model have SOEs with better performance and with lesser liabilities to GDP (a source of contingency risks for governments).

These problems are not new. The solutions we propose, however, are new and we think politically feasible. We document the problems of SOEs in LAC and show how countries that have adopted centralized agency monitoring of their SOEs, have managed to reduce the fiscal burden of SOEs, have shown consistently better financial returns, and have accumulated less liabilities to GDP, thus generating less fiscal risk for the government overall. We see a role to be played by financial markets in the monitoring of large SOEs, but all accompanied by strict administrative controls to contain the growth in SOE liabilities and to monitor their capital expenditures.

A new model of centralized monitoring and control

The fiscal risks that SOEs generate are too high to continue with systems of decentralized monitoring in which different line ministries do their own monitoring and in which there is no overall control of the size of contingent liabilities. Creating a centralized monitoring agency is like buying fire insurance, preventing governments from being vulnerable to fiscal crises of incendiary proportions, either in the short or in the long term. That is, not having control of what SOEs do is an invitation for unexpected bailouts, for having to make recurring fiscal transfers to cover losses, and for having a system that could potentially endanger the balance sheet and credit rating of the sovereign at any moment.

Rather than emphasizing the traditional agency problems of SOEs, especially asymmetries of information, we argue that reducing the discretionary nature of the fiscal relation between governments and their SOEs is key. Asymmetries of information have also to be alleviated and we recommend a variety of centralized reporting mechanisms and incentives that governments can use to improve what they know about their SOEs. Yet, without clear rules and timelines governing the fiscal relation between governments and their firms, the problems will simply continue.

The key for making work the SOE reforms we propose is political will. Politicians in the Executive and in Congress need to drive these changes. Therefore, we also need to create new incentives to politicians and the technocratic apparatus so they will be committed to obtain better results and decrease the fiscal risks derived from discretionary behavior and information asymmetry.

In many countries, the SOE departments at the Ministry of Finance or the SOE monitoring agency have the technical capacity and technological readiness to undertake the centralized monitoring of SOEs in the way we recommend. However, they do not have the political backing to do so. Line ministers, unions, and other stakeholders prefer less oversight from the Executive and Congress and to continue using SOEs for their own political agendas. Thus, the tradeoff is ultimately political.

Some policy recommendations

At the end of the day, we also acknowledge that centralized agencies and holdings are not a one-size-fits-all solution.

Some of our most critical policy recommendations are:

- Governments must improve the transparency and disclosure framework of SOEs to address information asymmetry. SOEs should be subject to strict timelines and standards to disclose financial data.

- Governments should use more sophisticated balanced scorecards that track the performance of SOEs and their managers and benchmark the quality of service of SOEs to improve performance monitoring in SOEs, using financial markets with and without privatization.

- For large firms or companies in complex industries, the best way to improve monitoring is to either partially privatize or to use state-contingent, quasi-equity instruments while adhering to the ex-ante controls and debt controls. For large firms whose privatization would be politically costly, quasi-entity instruments should be introduced to monitor and incentivize managers.

- For smaller SOEs, we have shown overwhelming theoretical and empirical evidence that a centralized agency or holding company that monitors or controls SOEs improves their performance and reduces fiscal risks. The size of these centralized agencies should remain relatively small and exclude SOEs for which monitoring requires sophisticated technical skills. The centralized agency should also operate with tight ex ante controls for debt issues and capital expenditure plans to reduce the fiscal risk.

- Governments should reduce the discretion of SOEs to issue debt and undertake large capital projects. SOEs debts should be subject to rules and ceilings. SOEs should also prepare annual budgets following international accounting standards with detailed projections of revenues, operational expenditures and all financial requirements.

Toda empresa se constituye para generar bienestar social, ganancias (Utilidades). lo que sucede que en el sector privado existe el control en la administración de sus empresas y los empleados tiene que responder a los accionistas. En las empresas del estado es el mandatario “Presidente” quien coloca gente de su partido de sus allegados ellos son los que manejan las empresas del estado que, uds, consideran ineficientes estos “analfabetos funcionales” son los llevan las riendas de estas grandes empresas son los que entregan las riquezas al sector privado Ejemplo PERU sus empresas estratégicas pasaron a manos del sector privado y encima no tributan no pagan impuestos. no hay empresas ineficientes son los personas las que lo llevan al éxito o al fracaso