Governments around the world have launched economic recovery packages in response to the recession brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Two key themes feature prominently: investments in digitalization and green technologies. Both China and the EU have established reactivation plans supporting 5G telecommunications networks, big data and artificial intelligence. The EU has further committed its recovery to moving the region towards carbon neutrality by 2050, including a massive expansion of the electric car market and related charging infrastructure. These demand drivers are expected to accelerate the arrival of the age of copper. The red metal conducts both heat and electricity and is a key input for global manufacturing electrical equipment, industrial machinery, and for construction. China’s post-COVID rebound has already translated into higher orders; in June 2020 China recorded the highest ever monthly imports of copper. Are copper producers prepared to leverage this new era for their development?

These trillion-dollar, multiyear recovery plans require significant quantities of copper. This will accelerate the demand for the metal which has picked up steadily since 2016 thanks to its central role in the digital, green economy of the future. Clean energy is the fastest growing segment to support electrification, with solar panels and wind turbines requiring some 12 times more copper than previous generation methods. E-vehicles use four times the amount of copper used in internal combustion engines. A Chinese national 5-G network will require some 72,000 tons of copper. COVID-19 has also brought copper to the forefront of the healthcare industry due to its antimicrobial properties, adding entirely new sources of demand. Even before the pandemic, it was estimated that the sector would drive 1 million MT of demand over the next 20 years. While 2020 demand may yet fluctuate as countries respond to the pandemic, the fundamentals of copper demand have changed for the better.

This boost in future demand is taking place against a backdrop of tightening supply in a globally concentrated industry contributing to a likely copper deficit. Five countries – Chile, Peru, Indonesia, Australia and Canada – export three quarters of traded copper concentrate. The two Latin leaders, Chile and Peru, are by far the most important to be able to meet new demand since they account for close to half of the world’s supply. Chile is home to both the world’s biggest copper mine, Escondida and the world’s single largest copper company, state-owned CODELCO. This company alone accounts for 10% of the world’s copper.

The impact of COVID-19 on the sector

Stung by end of the supercycle in 2012, CODELCO and other leading miners have operated conservatively; focused on consolidating their high value assets, cutting costs and boosting productivity, divesting from low-grade projects and limiting exploration and new project development. There are currently very few new projects set to come into operation before 2023. COVID-19 has brought the construction of most of these new projects to a halt. In Chile, CODELCO stopped the underground expansion of its two largest copper mines, El Teniente and Chuquicamata; Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca 2 announced a six-month delay as it sought to protect its 15,000 strong workforce. Peru’s largest new project, Anglo American’s Quellaveco, was brought to a standstill for months.

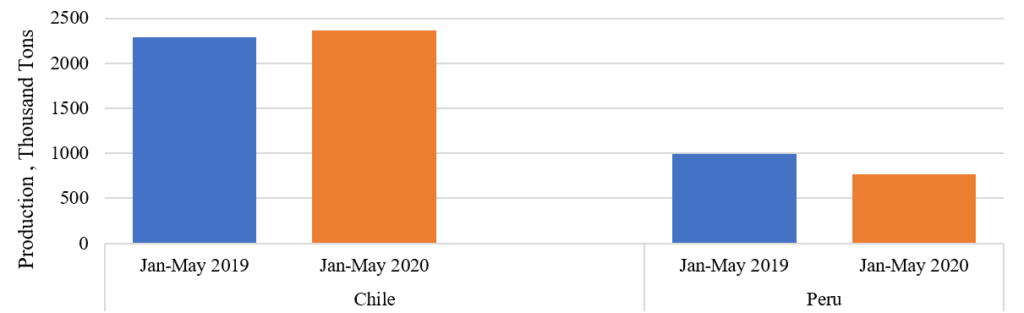

The shutdown of future projects exacerbates the impact of slowdowns in operating mines as a result of the disease. Between January and May, Peru’s copper output fell by 23% YOY as all of its major mines went into care and maintenance and 75% of its workforce went home in a nation-wide quarantine. While some of these went back to work by the end of July, output was still below 80%. Peru – the world’s second largest producer – estimates a 20% decline in exports for 2020. While there are concerns about Chilean producers facing similar crises, output to date has remained steady with a 3% YOY increase (Figure 1). Through the combined effect of shutting down existing operations and pausing new ones, COVID-19 in effect has pushed back the delivery of thousands of tons of copper, just at a time when demand is beginning to pick up. Despite the global economic contraction, copper futures hit their highest level in two years at US$2.97/lb in July as Europe announced its recovery plans.

Copper Production Jan-May 2019 vs 2020, Thousand Tons

Source: CoChilco, 2020; Banco Central de Peru, 2020.

Forecasted additional demand for the red metal represents an important opportunity

While copper directly contributes significantly to host-economies – it accounts for 50% of Chilean exports and 30% of Peru’s and approximately 10% of fiscal revenue– even greater spillovers can be harnessed. Mines have operated somewhat in isolation to their host economies and developing countries, in particular, have struggled to increase the benefits from their engagement in the value chain. Emphasis is often placed on increasing value addition through greater industrialization of raw materials. Copper producers, however, have shown uneven success in generating shared value around domestic metal processing. Returns on copper concentrate smelting, for example, remain relatively low as a result of significant global processing capacity, and refining encompasses significant environmental impacts. How to generate more value around mining activities remains a tantalizing question for industry and policymakers, and for civil society stakeholders – especially those wondering whether benefits outweigh social and environmental impacts and risks associated with copper mining.

In recent years, multiple experiences have shown that greater value capture may take place through development of strong backward linkages to the value chain by localizing the supply base in the host economy. The Chilean copper mining sector procures approximately US$12B on goods and services annually, while Peru’s miners spend US$9B. Currently, much of this is spent on foreign goods and services due to limited capabilities and opportunities for local suppliers. Yet, ranging from low value, simple options such as protective gear and grinding balls to excavators and highly complex engineering services, this industry offers a wide set of opportunities for local suppliers to participate. Australia, for example, has successfully tapped into this GVC upgrading option – it has developed a robust set of METS (Mining Equipment, Technology and Services) suppliers, investing US$2.7B in R&D to serve not only domestic mining operations but also export some US$10B. Most producing countries in the developing world, however, lag behind in this area. In the past five years, Chile has made some progress, launching the Alta Ley program, and Peru has recently launched a mining technological roadmap; with limited impact to date, considering the sector´s potential and stakeholder expectations.[1]

In this new age of copper, producer countries need to do better. Mining value chains can help them achieve ambitious innovation, sustainability and inclusiveness goals. Their development requires decisive and coordinated action from diverse public and private sector stakeholders. First, national mining innovation systems must be geared towards supporting existing and fostering new competitive suppliers, and fostering conditions for local players to access industry opportunities. Open innovation platforms can help bridge market failures and information asymmetries. Second, as the backbone of the future green economy, copper extraction itself has to become more sustainable, reducing GHG emissions and use of scarce water resources. It´s indispensable to obtain and maintain social licenses to mine, and to respond to increasingly sustainability-minded customers in the value chain. The industry is already actively seeking to adopt zero-emissions, waterless and desalinization solutions. Third, it needs to be inclusive – both from a gender perspective and engagements with local communities. Generating shared value necessarily means increasing participation from all key stakeholders and effectively leveraging local human capital. It´s not just good practice, it´s good business.

Latin America has been extremely hard hit economically by the COVID-19 pandemic. The economic reactivation plans of China and the EU can be leveraged to support the economic recovery of the region through their demand for copper. It is now up to these countries to seize the moment to upgrade within the copper GVC.

[1] See Bamber & Fernandez-Stark. (Forthcoming). Innovation and Competitiveness in the Copper Mining GVC: Developing Local Suppliers in Peru. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development.

Leave a Reply