By José Juan Gomes, Álvaro Concha, María Netto

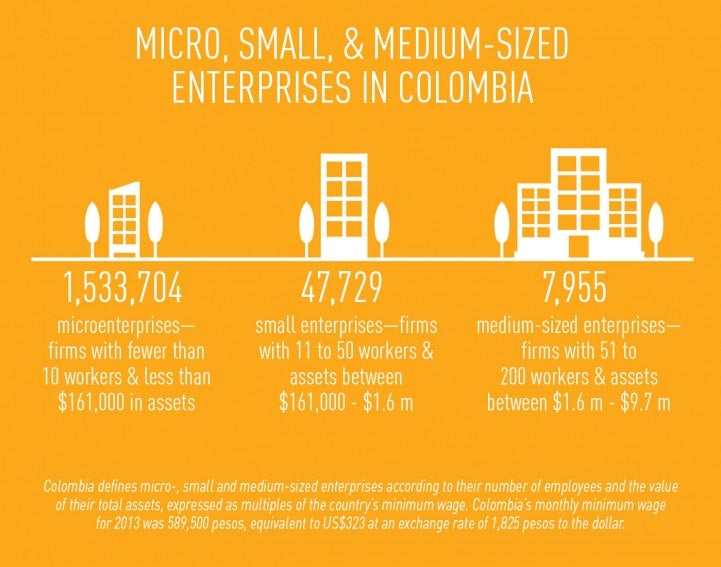

Nearly all of the estimated 1.6 million businesses in Colombia are micro, small, or medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). Across the board, if you ask owners of these firms what the biggest challenge is to grow their businesses, the answer is almost unanimous: access to credit.

Growth of MSMEs is critical to the Colombian economy because they generate more than 80 percent of the country’s jobs and 40 percent of its goods and services. Yet, because financial institutions often face a shortage of long-term deposits to fund their lending, they tend to focus their operations on large, well-capitalized firms, which are perceived as carrying lower risk than small or medium-sized firms.

To address this problem, Colombia has been expanding lending through Bancoldex, a government-owned development bank that is using an onlending strategy to funnel credit to smaller firms. Drawing on $300 million in long-term loans provided by the IDB since 2008, Bancoldex has channeled financing through regulated financial institutions to fund investment projects, productive restructuring, and promote development of business and export activities among MSMEs.

According to data from two IDB impact evaluations, Bancoldex’s strategy is working. The studies found that companies accessing Bancoldex investment lines get loans that are bigger and that carry lower interest rates and longer maturities than loans obtained by non-beneficiary firms. Moreover, the studies show that beneficiary firms have experienced increases in output, employment, investments, and productivity.

Sustainability

In addition to providing financing to Bancoldex, the IDB has worked closely with the bank to develop a full-fledged environmental and social sustainability strategy that includes improving Bancoldex’s own operations and developing green financing lines. Bancoldex has created a special team to manage the sustainability strategy and has developed internal systems to promote the analysis of environmental and social opportunities and risks in its portfolio. The bank has also set aside about $90 million to finance green projects for MSMEs, including renewable energy, energy efficiency, sustainable transport, water and solid waste treatment, and local pollution control and recycling programs. 58% of the Bancoldex green lines in 2012 were dedicated to MSMEs projects.

Bancoldex has also been innovative in the design of financial green instruments. A good example is the energy efficiency credit line for Colombia’s service sector, developed in partnership with the IDB and the Clean Technology Fund, which offers a series of different instruments so financial institutions channeling resources from this line can better manage risk and demand for this type of financing. The instruments include a concessional financing line, energy savings insurance, standardized contracts for energy efficiency projects that clearly define the rights and obligations of investors and technical service providers; and third-party technical reviews, monitoring, reporting, and verification of all projects.

By boosting credit to MSMEs and creating innovative products to improve sustainability, Bancoldex is helping MSMEs boost productivity—and helping Colombia overcome one of the biggest obstacles to its economic development.

Local Development Banks Can Improve Access to Credit

Government-owned development banks can play a crucial role in channeling public funds to MSMEs. Until recently, however, evidence to back up that claim has been scant and the few studies analyzing the impact of direct lending to companies by government-owned banks have shown benefits to be either nonexistent or even negative.

Two IDB impact evaluations found that results may be different for second-tier development banks such as Colombia’s Bancoldex, which channels resources through commercial banks at low cost so they can be on lent to firms. The studies, among the first to use highly disaggregated lending and firm data, analyzed the impact of Bancoldex lending on access to credit and economic performance of beneficiary firms over the past decade.

The first study found that firms tapping Bancoldex credit lines got loans with lower interest rates and longer maturities than firms that did not. Moreover, beneficiary firms expanded their credit relationships with other financial intermediaries, enjoying better credit conditions well after receiving Bancoldex’s credit.

The second study found that beneficiary firms in the manufacturing sector increased output, employment, investment, and productivity in the four years after they get their first Bancoldex loan. The effects were large, ranging from around 20 percent for employment and productivity to around 30 percent for output.

These results show that Bancoldex offers some “additionality” and does not simply substitute credit that private sources would be willing and able to offer under similar conditions. This suggests that Bancoldex is actually playing an important role in in facilitating access to credit. But what makes Bancoldex’s lending different than that of other government-owned development banks that have been less successful?

The reason is twofold. On one hand it may well lie in the fact that Bancoldex does not lend directly to firms. In contrast to the various forms of direct public support to businesses, credit from second-tier development banks is unlikely to be subject to political lobbying by potential beneficiaries. Loans are intermediated by commercial banks and other private financial institutions that take on the risk of default and, therefore, have all the incentive to perform an adequate evaluation of the prospects of the proposed projects.

On the other hand, Bancoldex—as other second-tier public bank—focuses its supply on products with high potential impact on firms’ performances, especially when resources are targeted to fund long-term projects.

The studies do call attention to some potential drawbacks to second-tier lending by government-owned development banks that should be carefully considered by policymakers. For example, financial intermediaries may be more willing to lend to firms with the lowest perceived risk and less prone to finance those that, despite good performance and prospects, have an insufficient credit history. This problem could be solved by creating special lines targeting the latter types of firms.

Overall, the two impact evaluations found that Bancoldex has shown that development banks can be an effective tool to help smaller companies access credit, as long as such banks refrain from lending directly to firms and concentrate their efforts on channeling long term resources through financial intermediaries.

Leave a Reply