If you knew that your commute was going to be slow and unreliable, and that you were likely to be attacked or sexually harassed, would you choose to work? This is the reality women face every day in many developing countries.

In Latin America and the Caribbean women are less likely to have access to a private vehicle and use public transit more often than men. They are also more likely to be victims of sexual harassment and crime in public transit systems.

In addition, since women still often bear most of the responsibility of household-related work, such as shopping, and taking care of children and the elderly, they tend to have more complex and intense transportation needs compared to men. Overall, longer commutes may be more likely to decrease the probability of women deciding to allocate time towards paid work in comparison to men.

If the quality of our commute affects our mobility decisions, then imagine how improving the quality, speed, and safety of public transit systems in Latin American cities might impact women’s employment rates, job quality and income.

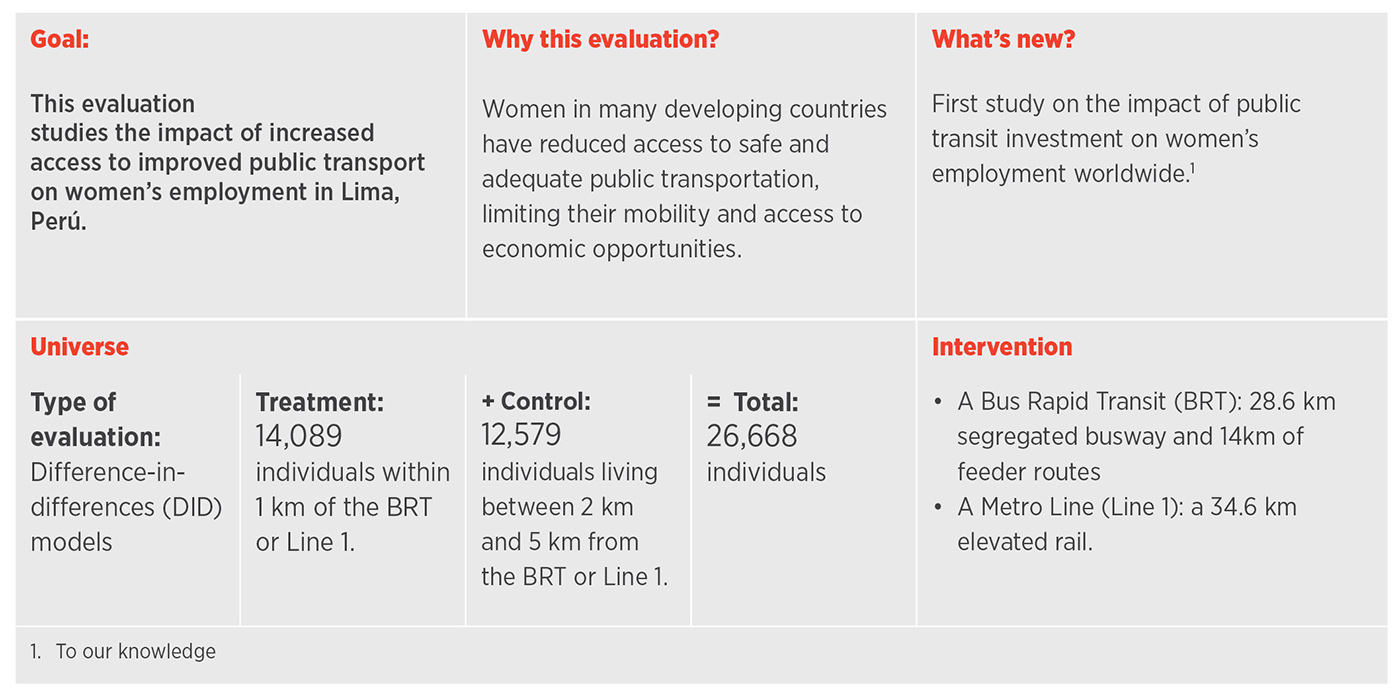

We set out to explore just that by taking a look at the opening of two new public transport systems in the city of Lima, Peru: A Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system and a new metro line.

Our study set out to answer the following questions: Are women (and men) living near either of these systems more likely to be employed after the systems were opened when compared to those living farther from the systems? And do they tend to have better jobs after the system opened?

The facts

Since the 1980’s, Lima, Peru, and its metropolitan area (Lima-Callao), has been strained by a highly chaotic and informal public transit system characterized by an oversupply of small minivans plying avenues in fierce competition for passengers, leading to high levels of congestion, accident rates and poor service overall.

Moreover, the rate of sexual harassment of women in the public transport system is one of the highest in the region. Seventy eight percent of female users of public transport reported being a victim in the prior year while traveling in a transit vehicle or waiting at a bus stop or transit station. Sixty four percent of women surveyed in Lima said that they felt insecure or very insecure in the city’s public transit system, and 77% reported feeling unsafe when traveling at night.

In terms of jobs, there are large gender differences in employment rates between men (80%) and women (60%) in Lima. Women are more likely to be homemakers, to be self-employed, and have jobs that are lower quality and poorly paid. Over 70% of women—as opposed to 50% of men—have informal jobs, that, by definition, do not include social security or benefits.

Improving transportation in Lima

In 2010, the city launched a new modern BRT line, and in 2012 Lima’s Line 1 of the metro system opened. The two systems not only substantially reduced travel times and connected residents in outlying areas to core job centers, they also included several important features to increase the personal security and safety of passengers.

Both systems have security cameras in vehicles and a system for reporting crimes on board and at stations. Stations are well lit and have guards and staff on-site. Drivers receive formal training, wear uniforms and can communicate with the central operating center in the case of an issue. We believe that these changes may have strongly encouraged women to use these systems and significantly improved their accessibility to jobs when compared to men.

How did we tackle the question?

To explore this possibility, we compare average employment rates and earnings of women and men who live in areas within walking distance from the new systems versus those living in comparable (control) areas that are farther away, and analyze changes for both groups in the years just before and for several years after they opened.

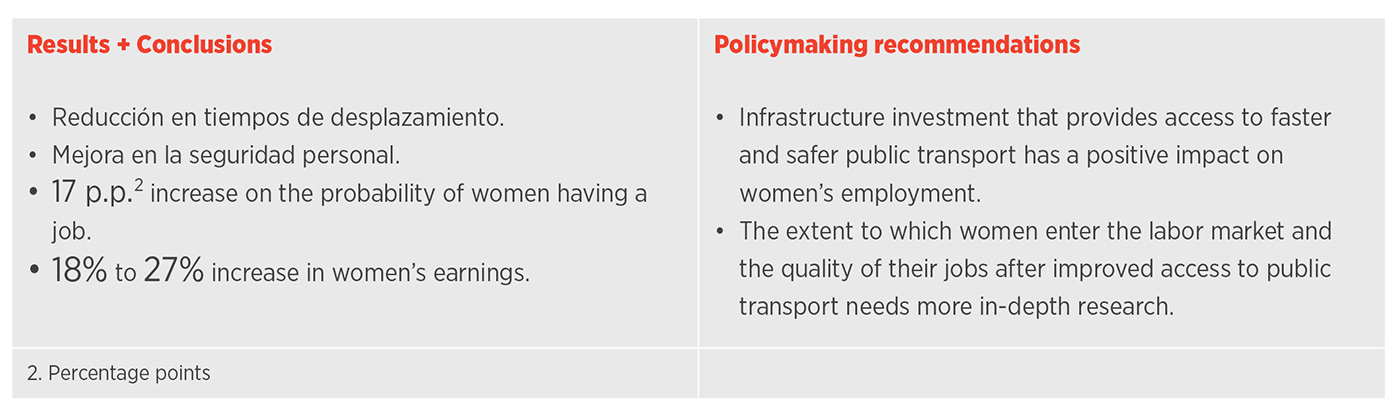

We find that women who live within walking distance of a BRT or metro Line 1 station are much more likely to use public transit, to be employed and to earn more after the systems opened, compared to women in the same areas prior to the systems opening, as well as compared to women in the control areas. We do not find any significant effects among men.

The impacts on women tend to increase over time. From 2012 to 2014, just after the BRT and Metro Line 1 opened, the impact is of an increase in 8 percentage points on the probability of having a job, while it doubles to around 17 percentage points in later years, from 2015 to 2017. To unpack these numbers, the probability of being employed changed for women in the areas close to the BRT and Metro Line 1 from 65.5% to 69.9% from 2007-2009 to 2015-2017, while in the control areas labor force participation of women decreased from 73.4% to 67.7% in the same period. The impacts on earnings are large, with an 18% increase in average earnings initially, and a 27% increase in the 2015 to 2017 period (this translates to an increase of 307 soles in the treated area, roughly US$ 90 in 2017).

We believe the observed employment benefits can be attributed to one or a combination of two reasons: faster travel times and/or that women felt safer in the new public transit systems. Indeed, recent surveys of female transit users in Lima indicate that shorter travel times as well as increased security are two of the most frequently mentioned reasons for using the BRT or the Metro.

Due to data limitations, we cannot disentangle to what extent one factor influenced the observed benefits over another. Nevertheless, what is clear is that infrastructure investments that make public transport faster and safer can generate important labor market benefits for working-age women with access to modern modes of public transportation.

To learn more about IDB Group’s projects in Latin America and the Caribbean, download the 2019 Development Effectiveness Overview, the institution’s flagship publication on results and impact.

Leave a Reply