Research studies from a range of countries indicate that, despite differences in policies, youth who age out of state care face similar social and health challenges globally. These young people have difficulty finding stable, affordable housing; accessing social networks, health care, supportive and safe social relationships; and engaging in education, training, and employment. A report from the UK National Audit Office indicated significant difference in outcomes between care leavers and other young adults:

- 41% of care leavers were not in education, employment or training (NEET) compared with 15% for all 19-year-olds.

- 6% of care leavers were in higher education compared with one-third of all 19-year-olds.

- 49% of young men under the age of 21 who had come into contact with the criminal justice system had a care experience

- 22% of female care leavers became teenage parents; and

- Care leavers were between four and five times more likely to self-harm in adulthood.

“Young Adults Formerly in Foster Care: Challenges and Solutions”, a Youth.Gov brief, indicates youth with foster care experience in the United States face similar challenges:

- More than 20% experience homelessness within a year of emancipation;

- Only 3% receive post-secondary education;

- Approximately 33% have mental health disorders; and, according to one study,

- 45% percent had been in trouble with law enforcement, 41% percent had spent time in jail, 26% percent were involved in the court system (with formal charges filed), and 7% were incarcerated.

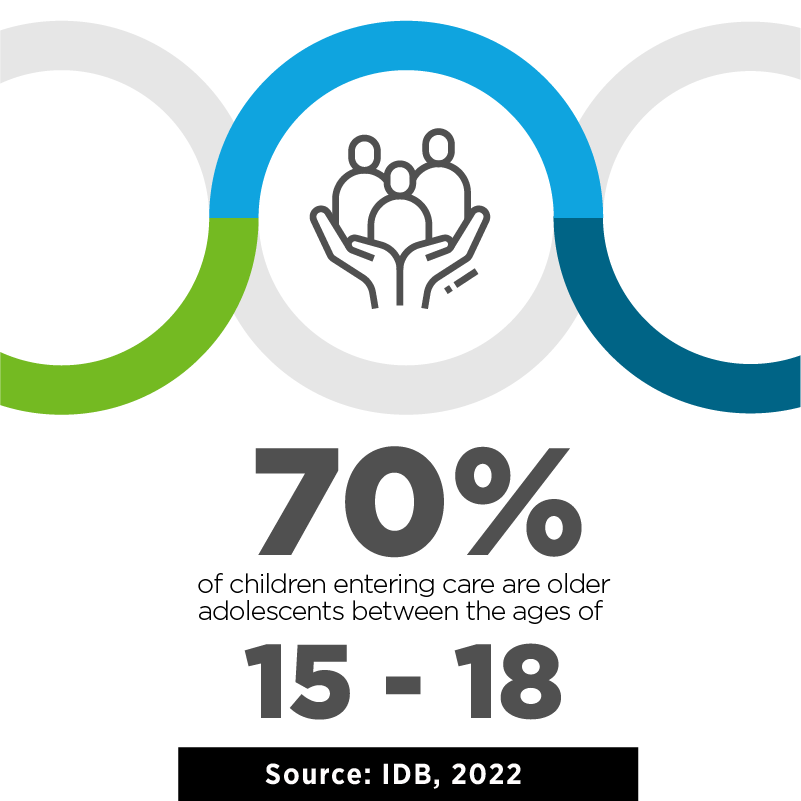

In Belize, a recent IDB-financed study by Coram International found approximately 70% of children entering care are older adolescents between the ages of 15 and 18. The majority live in non-family settings – residential homes or at the youth rehabilitation center – and need support to transition to post-care independent living.

Comprehensive data on outcomes for these youth once they leave is not available. Yet, anecdotal information indicates that, similar to countries across the world, Belize faces challenges providing arrangements that ensure the well-being of children transitioning out of care. At the request of the Ministry of Human Development, Families, and Indigenous Peoples’ Affairs (MHDFI) of Belize, the IDB commissioned a study of available services to support youth aging out of care.

The resulting report provides a set of operational, programmatic, and policy recommendations to strengthen the services to support youth to transition to post-care. While many are specific to the Belizean context, they provide a useful framework that can serve other countries in the region that are seeking to improve outcomes for their most vulnerable youth.

Six key takeaways for other systems in the region to improve life experiences for vulnerable youth in state care:

1. Foster children’s family and community connections while they are in state care.

Policies and procedures for managing children in care must strengthen children’s ability to maintain stable community and family relationships. Actively promoting children’s continuous contact and relationship with safe, adult family members; avoiding placements that separate children from siblings or friends to whom they are attached; and encouraging children to receive and visit friends from the community at home improve the child’s chances of developing and maintaining family and friendship networks that can support them once they leave care.

2. Increase the age until which care-experienced youth receive assistance.

. It is not uncommon for adults in Belize, as well as many other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, to remain living with their parents until they are married or have a child. In contrast, upon leaving care at 18 years of age, youth formally in care lose housing as well as financial, social, and educational support at a younger age than other youth leave home, all while dealing with the trauma experienced before and in care.

The loss of a stable home coupled with the lack of family or social networks significantly increases care leavers’ vulnerability. For this reason, assistance with accommodation, maintenance, education and health costs, as well as social work support until at least the age of 21 and, where needed up to age 25, enable care leavers’ to successfully transition to independence.

While noting the increased costs associated with extending assistance, the Report notes that the lifetime costs of not providing support to care leavers may – including the costs of homelessness, involvement in the criminal justice system, unemployment, poor health, drug and alcohol abuse, and the creation of new, unstable family units – may be higher.

A study from the Annie E Casey Foundation found that each young person leaving care at 18 in the US cost the State $300,000 in welfare, Medicaid, lost wages, and incarceration costs compared to people of the same age who were not in foster care. Other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are beginning to extend support to children in care after 18 years of age, in recognition of the costs of not doing so. The Supreme Court of Colombia has held that the protection system retains responsibility for adolescents that have not been reunited with their birth families or been adopted until they become independent and must continue to provide support to prepare the youth to work and have positive social integration in a similar way as is expected of the biological, adoptive or foster family.

3. Develop a suite of support options for youth leaving state care.

All stakeholders interviewed for the study agreed that support was needed to enable youth leaving care to adapt to independent living. Importantly, the options of support should reflect the diversity of care leavers’ needs and specific support tailored to each youth.

Options to explore include continuing therapeutic support; developing a pipeline of community supporters from supportive landladies to rent accommodation to care leavers to adult sponsors and mentors; extending the period of stay in the residential care home to the age of 21; providing supported independent housing with non-care leavers; and the staying close option, where the child would live independently but near the residential home, with access to continued support from one of the home’s social workers and the option to return to the home for meals and activities if desired.

4. Reduce the pipeline of care leavers needing to transition to independence by actively pursuing alternatives.

One alternative to children’s transition to independence is promoting the institutionalization in residential homes or rehabilitation services. Some of this work is currently in train in Belize. A proposed move to abolish the placement of children in the Youth Hostel under uncontrollable orders and the increased use of the diversion for children in conflict with the law are clear steps forward.

However, for children in child protection systems, more can be done to reduce reliance on group homes and to move them into family-like settings where they can develop attachments and support from consistent, nurturing adults.

A Casey Family Foundation brief notes the limited and short-term effectiveness of group and institutional placement and advocates for offering the services provided there in “family-like settings through therapeutic foster care, wraparound services, and mobile crisis services.” In doing so, it points to evidence in the US that indicates significantly worse outcomes for youth who experience group placements than those in family settings; including 250% greater likelihood to become delinquent, poorer educational outcomes in terms of school achievement and completion; and lower likelihood of achieving permanency.

5. Strengthen data collection on youth in care and care leavers to understand the outcomes of policies and programs

Key data to gather includes length of stay, accommodation setting, educational achievement, employment, health concerns, and social connectedness. These should be complemented by qualitative evaluations of the leaving care services offered, to ensure that the services are effective and meet the needs of children leaving care.

6. Develop a national policy on leaving care with youth in care and care leavers.

Establishing a national policy is key to developing a framework for action that identifies the systemic issues preventing successful transition from care and the steps to be taken to ensure success. However, particularly given the lack of data on care and its outcomes, it is critical that youth in care and care leavers be formally engaged in this process.

The Report recommends the development of a youth-led organization for youth in care and care leaversto represent children’s interests in the care system at the policy, legislative, or practice level and/or to provide self-help to this group of children and young people.

This type of organizations are important avenues for children’s experience of care and transition to be heard. The Report notes that these organizations exist in different forms in other countries and provide “a conduit or instrument through which young people can talk about their experiences of being in care, feel supported by peers and professionals, and have their opinions taken into account in policy discussions and service delivery.”

What is the IDB doing to improve outcomes for children in care?

The Inter-American Development Bank has a multisectoral agenda that includes support for the strengthening of social protection systems and providing opportunities for at-risk populations such as youth in care through social violence prevention programs. This work has focused on children currently, or at risk for being, in conflict with the law.

In Belize, specifically, the Bank financed the Community Action for Public Safety program with the aim of preventing and reducing youth involvement in criminal activities and violent behavior as well as reducing recidivism among youth in juvenile rehabilitation facilities. The program, which closed in 2017, supported creation of a continuum-of-care model for juvenile offenders and a series of educational and recreational centers for youth who were neither studying nor working, to support positive youth development.

For the most part, as in other parts of the region, the Bank’s work in Belize has focused on children and youth who were either living with their families or in detention facilities.

The current study, financed by an IDB grant, aims to expand and deepen the Bank’s work with vulnerable youth in Belize by including a previously overlooked population: youth in the child protection system. The study highlights the urgent need to support this segment of the youth population and lays the groundwork for an important new agenda in this area.

Leave a Reply